ORCS IN A NEW MEDIUM

I was surprised and delighted to be presented with these coasters and collector cards, drawn from my Orcs series, by gifted artist Ky Crout. Ky's based these on various of the book jackets, and character studies by Chris (Fangorn) Baker. I never cease to be impressed by the amazing talent out there, and to be grateful for the generosity of readers.

Here's the source for the above (US cover of the first Orcs trilogy):

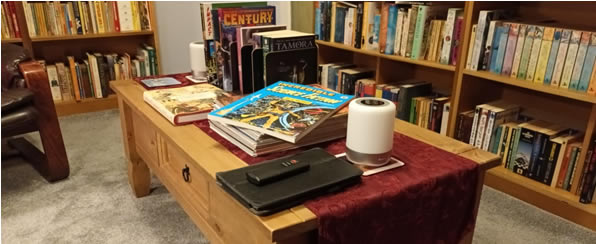

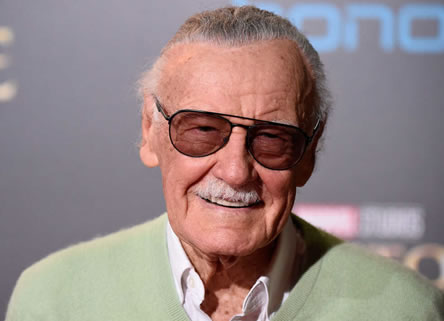

PHOTOGRAPH OF THE MONTH (67)

A garden reading nook, for what passes for Summer here in the UK

You can view all the previous Photographs of the Month in the Photo Gallery.

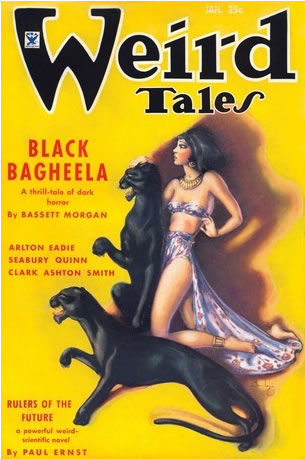

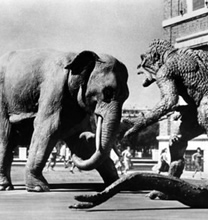

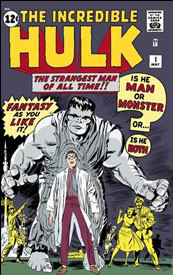

STILL CREEPY AFTER ALL THESE YEARS

A couple of weeks ago someone kindly got in touch to tell me they'd just bought a copy of Warren Magazine's Creepy issue 19 (March 1968), pictured above, in which they spotted a letter by me. I'd completely forgotten about this. I was just a kid at the time, you understand, and looking at it now I'm struck by what a self-opinionated little know-all I was.

The glaring scrambled sentence in the above was down to the magazine, BTW, not me.

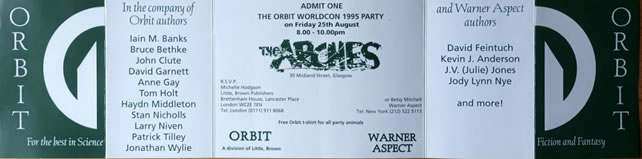

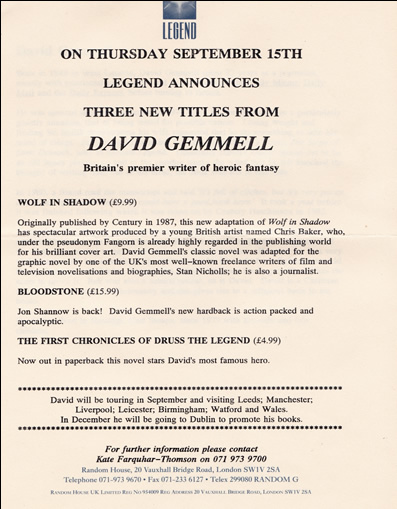

THUNDERBIRDS WERE GO

I just unearthed some flyers from the 1996 tour I undertook with Gerry Anderson for the biography.

As stated in the bibliography section of this website:

This project was born of tragedy. Simon Archer was a local radio presenter and a huge fan of Gerry Anderson’s TV series. Gerry agreed to Simon writing his authorised biography, but shortly after he began, Simon lost his life in a car accident. I worked from Simon’s notes, coupled with my own interviews with Gerry, and turned in the book against what had become a pretty tight deadline. There was another Gerry Anderson authorised biography a couple of years later by another writer who incorporated elements of my work and Simon’s. I wasn’t involved in that.

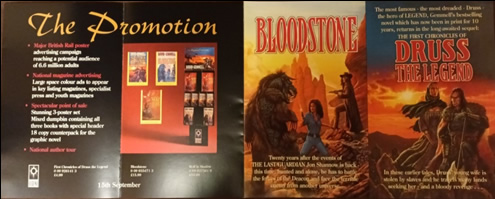

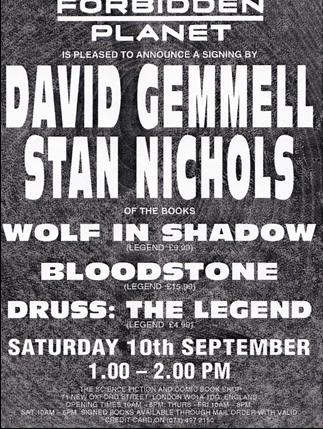

AND IN THE SAME BOX …

… this copy of Comic World magazine that covered the launch of the graphic novel version of David Gemmell's Legend, which I adapted. A pity they misspelt Gemmell's name on the cover. But just so I wouldn't feel left out they did the same with my name inside. Nice coverage though, to be fair.

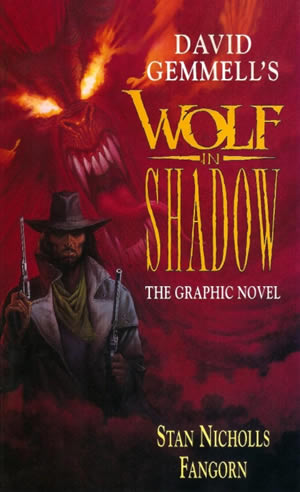

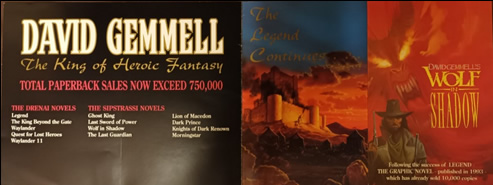

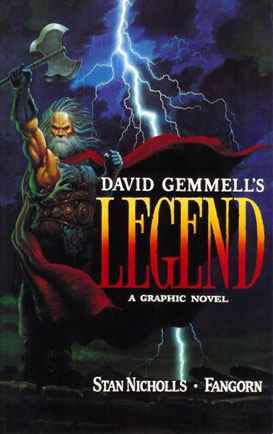

ON THE SUBJECT OF GRAPHIC NOVELS

A correspondent alerted me to this YouTube channel containing a page by page examination of the graphic novels of David Gemmell's Legend and Wolf in Shadow - which I adapted and Chris (Fangorn) Baker illustrated - with commentary (in French). You can find it here.

A BLATANT REMINDER

That my story Dreaming in Babylon can be found in the current issue of e-zine ParSec. Details here.

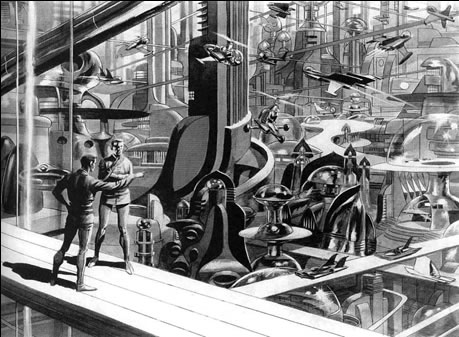

PHOTOGRAPH OF THE MONTH (66)

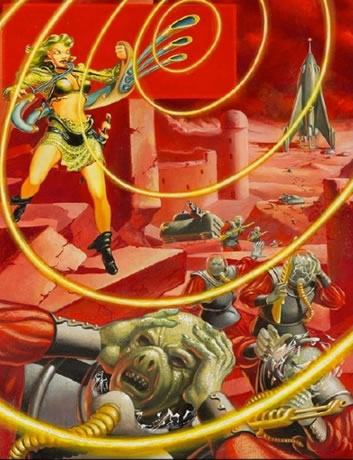

I took this on a visit to Dubai in 2011. It struck me how the city resembled a science fiction pulp magazine cover.

You can find all the previous Photographs of the Month in the Photo Gallery.

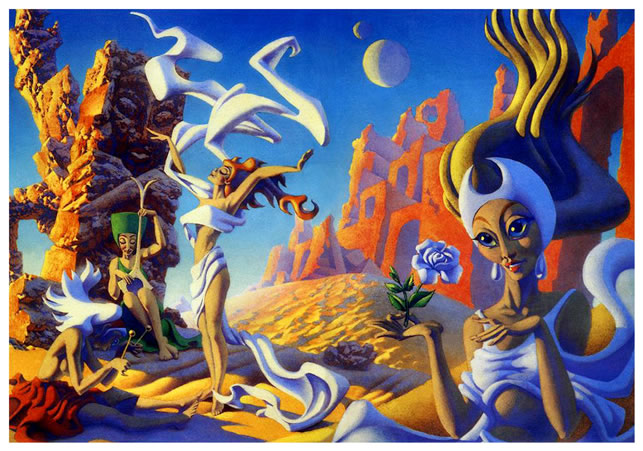

PARSEC 10 COVER REVEAL

I mentioned in last month's update that I had a story, Dreaming in Babylon, in issue 10 of ParSec magazine, which was published on 26th April. Here's the completed cover, with a fine piece of artwork by Jim Burns. You can find out more about ParSec, includingordering information, here.

And for a limited period there's a promotional discount offer, explained here by publishers PS Publishing

25% DISCOUNT!

“Just to refresh everyone, ParSec is our digital magazine featuring the latest fiction from established writers alongside the best new stories from emerging talents and debut authors. It includes on-point articles and regular columns, exploring genre fiction in all its forms, and interviews with leading authors and artists. Plus insightful and informative book reviews on current titles and imminent releases from publishers big and small. This magazine sports a lot of heft, considering its 3 short years of existence.

“We've reached out to a couple of reviewers to promote the magazine and the calibre of content on offer within each issue, and with the help of Matt Cavanagh at Runalong The Shelves here we have a blog tour of ParSe.

“If you start with this link, you'll follow the tour below:

• Mark’s review of issue #1 at Fantasy Book Nerd, which links to

• Jonathan’s review of issue #2 at Fantasy Hive, which links to

• Alex’s review of issue #3 at Spells & Spaceships, which links to

• Kayleigh’s review of issue #4 at Happy Goat Horror, which links to

• Isabelle’s review of issue #5 at The Shaggy Shepherd, which links to

• Kiki’s review of issue #6 at KB Book Reviews, which links to

• Matt’s review of issue #9 at Runalong The Shelves

“Each review includes a discount code for 25% off ParSec issues #1 - #9. Just copy and paste the discount code at the checkout and download for £4.49 each. Compatible with all e-readers.

“Now buckle up and begin!”

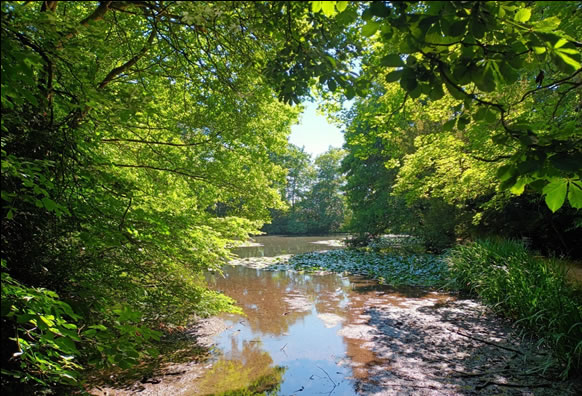

PHOTOGRAPH OF THE MONTH (65)

Spring, and the return of green.

All previous Photographs of the Month can be found in the Photo Gallery. I also regularly post photographs on my Facebook page.

Every monthly news update from 2008 to the present can be found in this site's archive here.

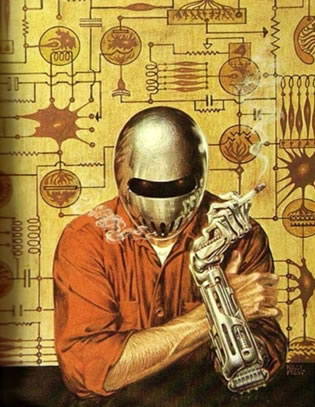

This illustration, by renowned sf artist Jim Burns, will appear on the cover of Parsec magazineissue 10, which I'm very pleased to say includes a story by me entitled Dreaming in Babylon. Parsec's rapidly grown into arguably the UK's best science fiction/fantasy magazine (I don't say that because I'm in it!) and you can find details here. Issue 10 appears later this month and the complete cover isn't available yet. I'll post it here next time.

COMPLETE ORCS OFFER

For UK readers with Kindles: “The complete ORCS saga - containing all six novels and one short story - is perfect for fans of fast-paced fantasy action.”

The Kindle edition is now £14.99. Not bad for over 1600 pages. See here

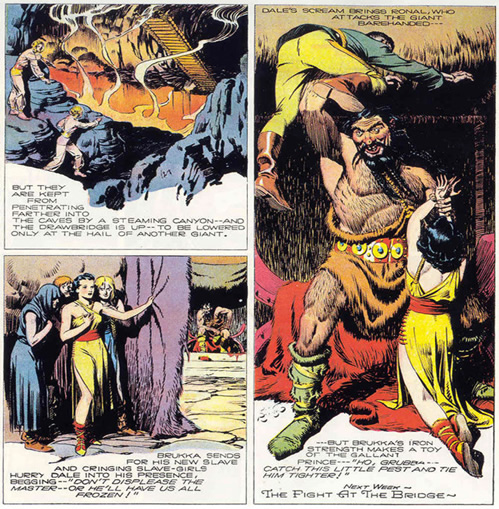

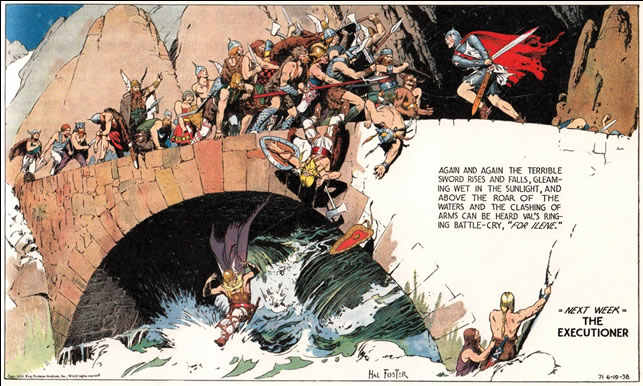

FAVOURITE ARTISTS 11

Just one entry this month in my series of personal favourites that began in the June 2023 update, and which also runs regularly on my Facebook page.

Favourite Artists # 36

JON SULLIVAN (d.o.b. unknown)

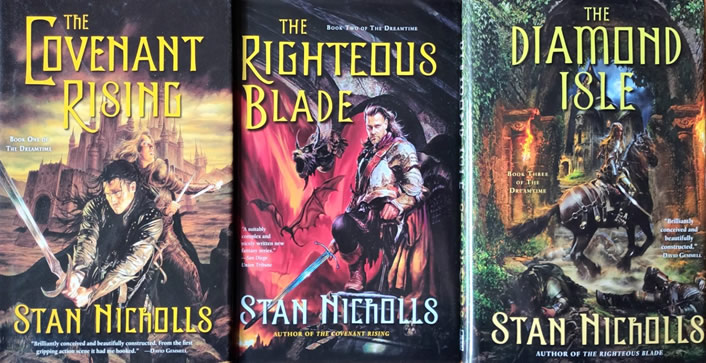

I know practically nothing about painter and sculptor Jon Sullivan beyond the fact that he's South London based, that he did a lot of illustrations for the Warhammer 40K series, and that he produced a number of outstanding covers for fantasy and science fiction books. He's also very affable. In this digital age, when we know just about everything about almost everybody, it's kind of refreshing to come across someone who prefers to keep themself to themself. It allows their work to speak for itself.

The first illustration here is City Wars, and Devil in Green is below that. Both are oil on board.

Disclaimer: Jon produced the covers for the American editions of three of my books, which are among the best I've been fortunate enough to have. But he'd still be in this series if he hadn't.

Jon Sullivan provided the covers for the American covers of my Quicksilver trilogy

(re-named the Dreamtime trilogy in the US):

PHOTOGRAPH OF THE MONTH (64)

The Cotswolds this month. Bourton-on-the-Water, in the county of Gloucestershire.

You can see all my Photographs of the Month, going back to January 2019, here. I also regularly post photos on my Facebook page.

WELCOME ADDITIONS TO ANY GEEK HOUSEHOLD

We recently received these beautifully made figurines of David Gemmell characters Jianna and Druss, courtesy of gifted modeller Simon Cook. Simon is one of the stalwart moderators at David Gemmell Fans, the leading Facebook group dedicated to the legendary fantasy author. If Gemmell's fiction appeals to you I highly recommend this knowledgeable, convivial group.

FAVOURITE ARTISTS 10

Here's the continuation of the series of personal favourites I began with the June 2023 update (scroll down to find it) and which also runs regularly on

my Facebook page.

Favourite Artists # 32

RYAN SOOK (d.o.b. Unknown).

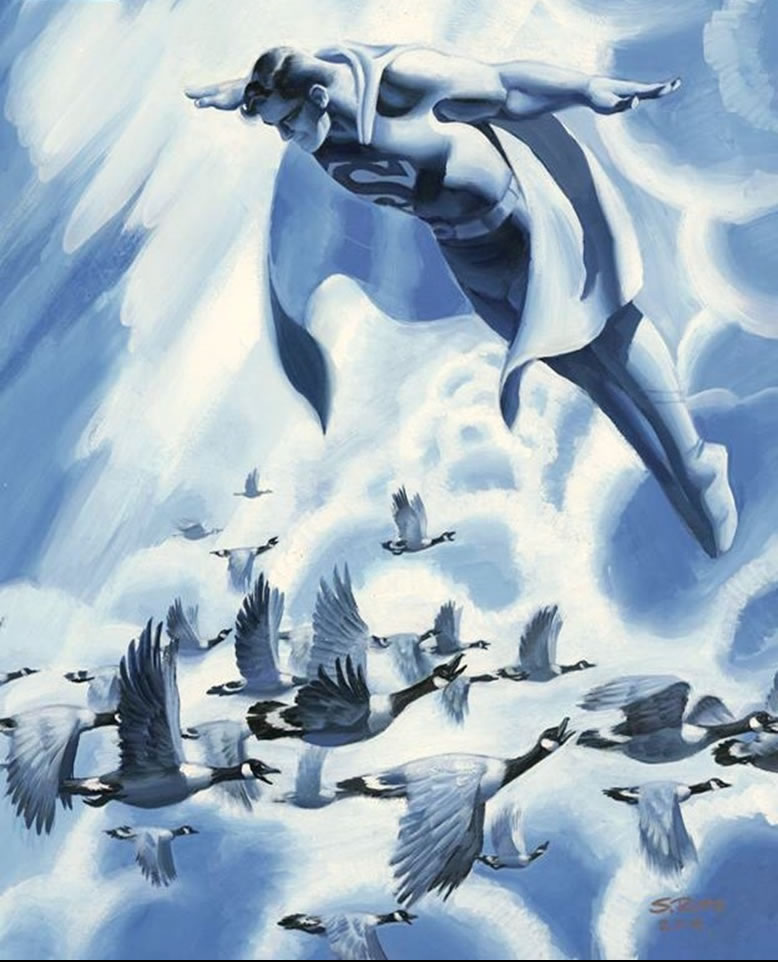

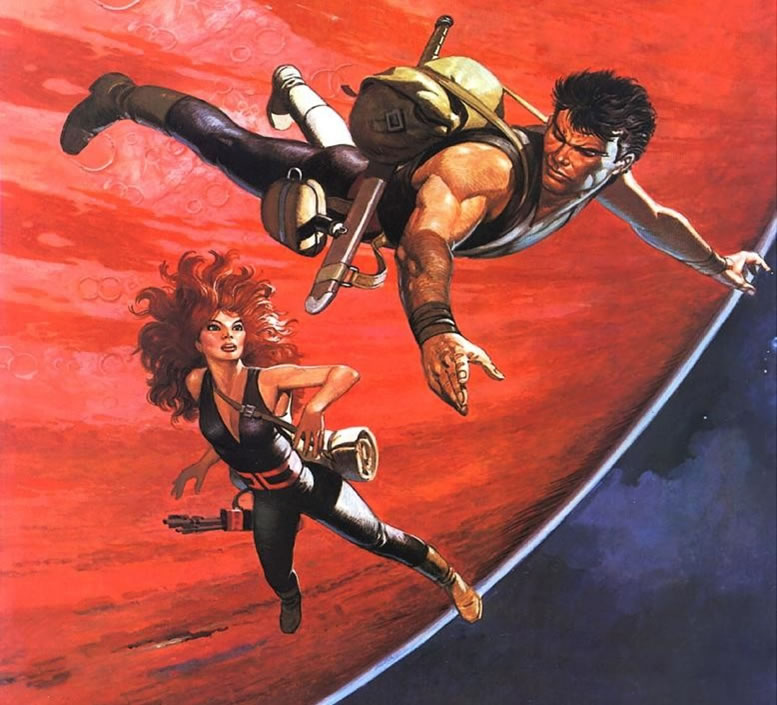

The first illustration below is the cover artwork for Action Comics no 1004 (December 2018), which I think has genuine charm. The second is entitled Lois & Clark: Fireworks!, a print taken from a VS System Trading card game. I'm also including the complete Action Comics cover the first illustration is taken from.

San Jose, California born Ryan Sook’s first professional commission was for DC’s Challengers of the Unknown number 15 (1998). He has worked for most of the major comicbook publishers and his many credits, for both interior and cover artwork, includes depictions of Batman, Buffy the Vampire Slayer, the Flash, Green Lantern, Hawkman, Hellboy, Jonah Hex, The Legion of Super-Heroes, the Spectre, Spider-Man, Superman and Thor.

Favourite Artists # 33

DON (SOUTHAM) LAWRENCE (1928-2003).

The first illustration below is The Fall of Samaria. The second is Pirates.

After national service in the army, Don Lawrence studied art at Borough Polytechnic (since renamed London South Bank University) but didn't pass his final exams. He found work with Mick Anglo, who ran a studio packaging comic strips for publishes. During his four years with Anglo Lawrence drew various western strips and Marvelman. Moving on to Odhams and Amalgamated Press (later Fleetway) he drew a variety of historical adventure strips, including Maroc the Mighty, written by Michael Moorcock.

In 1965 Lawrence began his most celebrated strip, The Rise and Fall of the Trigon Empire, for the titles Ranger and Look and Learn, which ran until 1976. That year, at a London comicbook convention, he learned that The Trigon Empire was being widely syndicated abroad, but in a scenario all too familiar to freelance illustrators, his publisher refused to pay him any royalties. He quit and took employment with several Dutch publishers. During this period he produced another notable strip, Storm, in partnership with writer Philip Dunn. He also drew strips for TV Century 21 and Mayfair magazine, among others.

In 1995 an unsuccessful cataract operation caused him to lose sight in his right eye. He was later diagnosed with emphysema and died from the condition at age 75. Lawrence garnered a number of awards, including 1980's Society of Illustration Lifetime Achievement Award.

Favourite Artists # 34

MICHAEL ENGLISH (1941-2009).

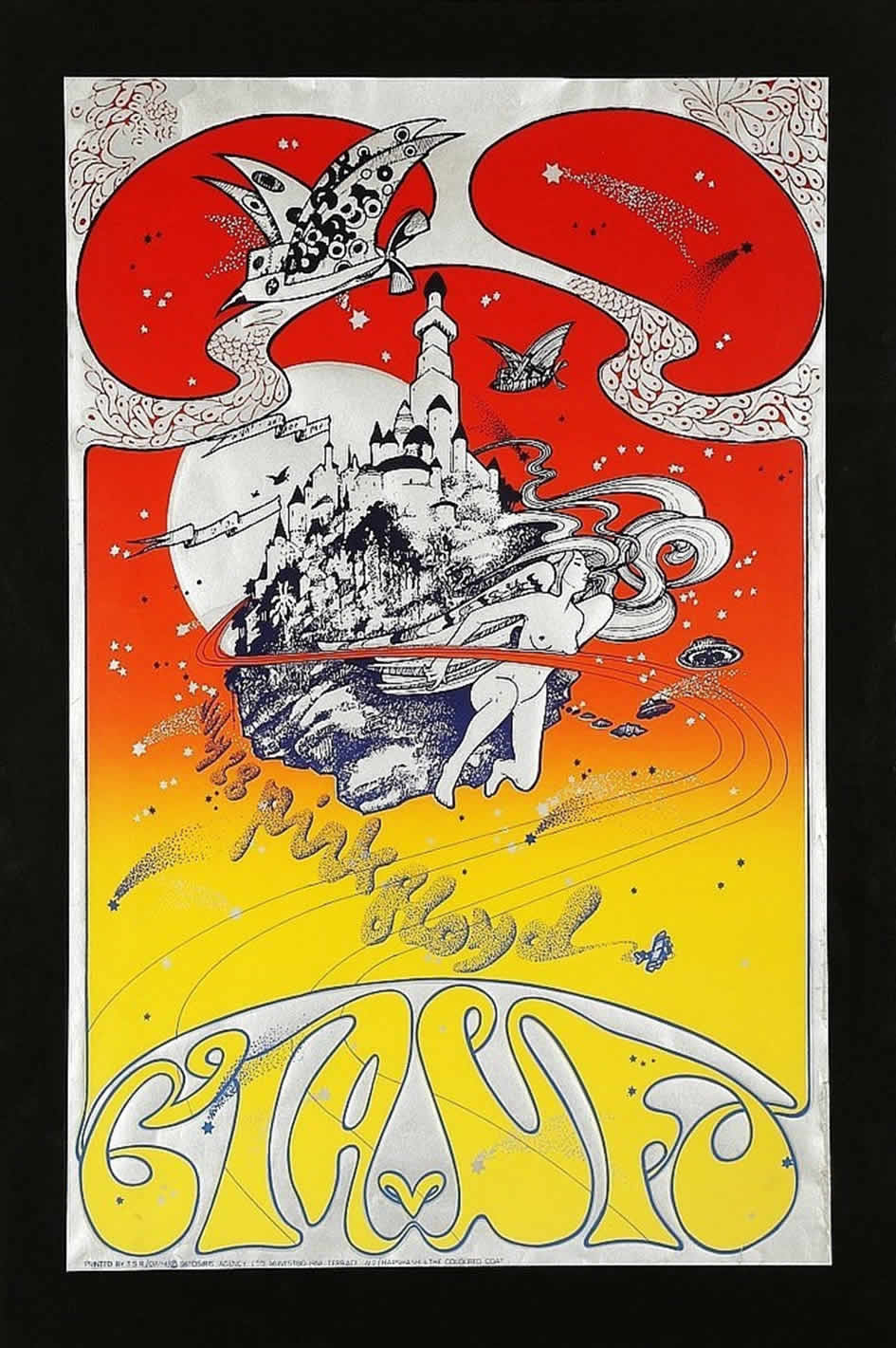

The first illustration is Heinz (1970). CIA vs UFO (1967), a poster advertising a Pink Floyd gig at London's UFO club, is the second.

The son of an RAF officer, Oxfordshire born Michael English's childhood was spent in a number of different UK locations depending on his father's postings. Fascinated by drawing from an early age, he entered Ealing College of Art in 1962. At the dawn of “swinging London” in 1966 he created murals for several iconic shops of the period, including King's Road's Granny Takes a Trip. In 1967 he was co-founder of graphic design company Hapshash and the Coloured Coat, where he produced poster art for bands and music festivals. He also provided illustrations for underground magazines International Times and Oz. In the 1970s he moved from so called Pop Art to Hyper Realist paintings that in the vernacular of the time sought to “make the everyday sensational”. He was a pioneer in the use of the air brush in these “food paintings”. Later in life he designed sets of postage stamps featuring London buses (2001) and vintage motorcycles (2004).

As I was a member of Tottenham Court Road's UFO club, and having attended the Pink Floyd concert in question, I couldn't resist using the poster.

Favourite Artists # 35

JOSE “PEPE” GONZALEZ (1939-2009).

The first illustration is She, the Vedette. James Dean is the second.

Spanish comic book artist Jose Gonzalez began his career at age 17, working for the publisher Editorial Toray on the titles Brigitte and Rosas Blancas. When he was 21 he joined art agency Seleccones Illustrades, which led to commissions from UK's Fleetway, mostly on romance comics. He is best known for his work on Warren Publishing's Vampirella, starting with issue 12 in 1971 and continuing until issue 34, producing 53 strips featuring the character. He won the Warren Award (for best story art) in 1971 and 1974. Warren also reprinted Gonzalez's three part series Herma, which first appeared in issues 8 to 10 of the magazine 1984.

No longer being a libidinous teenager I find Vampirella a little too cheesecake for my tastes, despite its artistry, and prefer Gonzalez's other work, as here.

PHOTOGRAPH OF THE MONTH (63)

The first flush of Spring and life returning.

A REMINDER …

… that this website has more departments than you might be aware of. They can all be accessed via the menu at the top left of the screen. Or directly via these links:

My biography

A bibliography of my books, in these sections:

The Orcs series

The Quicksilver trilogy

The Nightshade Chronicles trilogy

Other titles

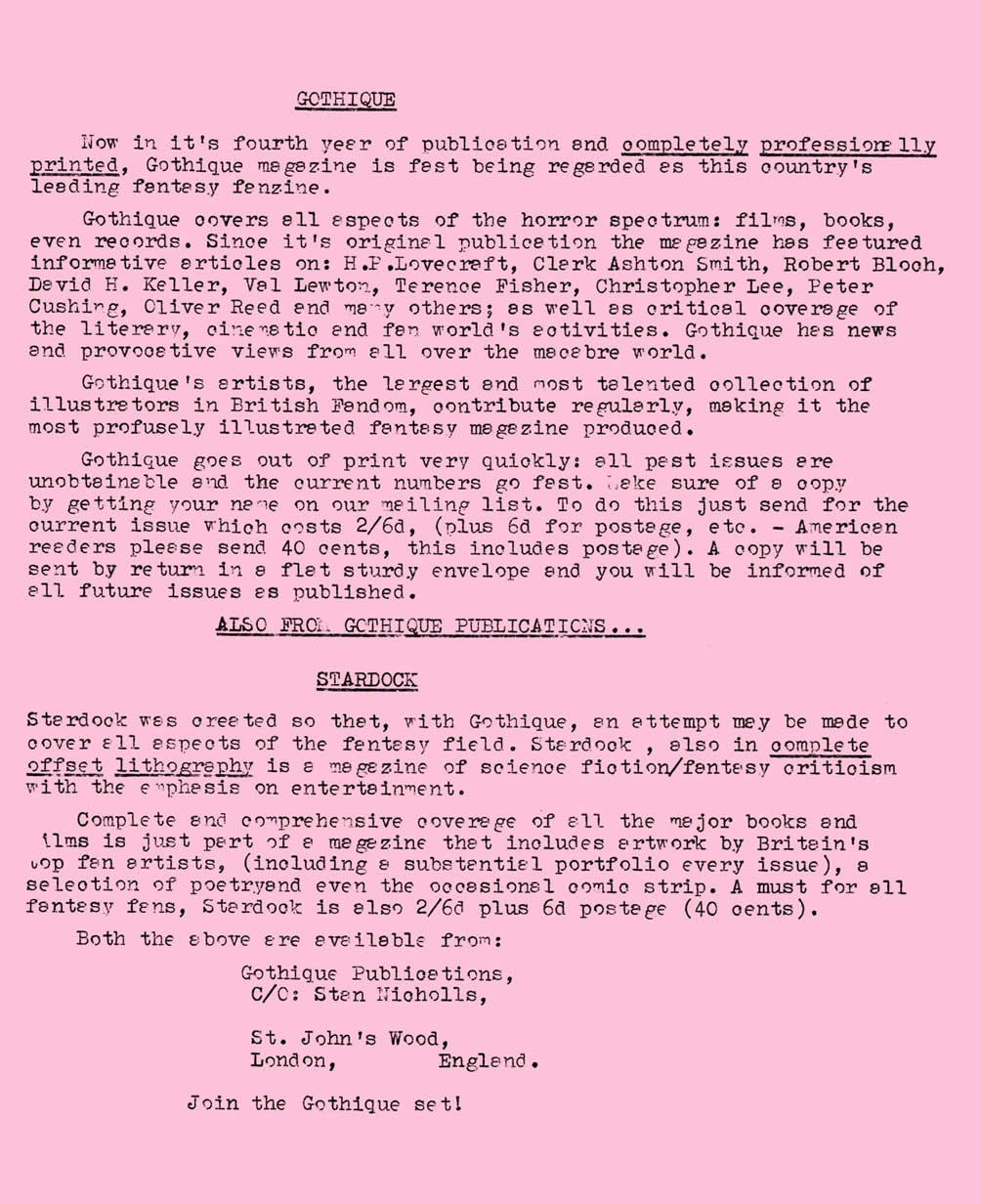

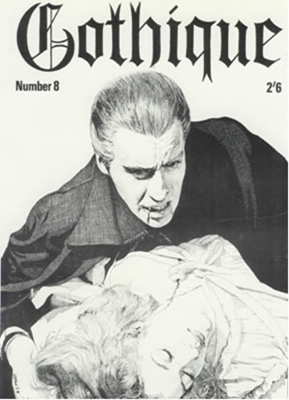

Gothique and Stardock magazines

A photo gallery in these sections:

Photograph of the Month

Conventions and other events

The David Gemmell Awards For Fantasy 2009-2018

New Archive going back to 2015

You'll also find a way to contact me in the menu.

Artwork by Didier Graffet

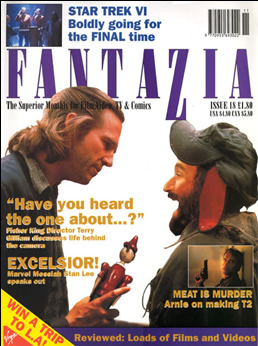

EPHEMERA

From the archives. I think this flyer, distributed at conventions, is from around 1969. If you want to know more about Gothique and Stardock – the fanzines I and others published when we were mere striplings – there's a section of this website devoted to them, here.

They might have been a bit crudely produced and verging on embarrassing in their youthful innocence, but I was proud of them.

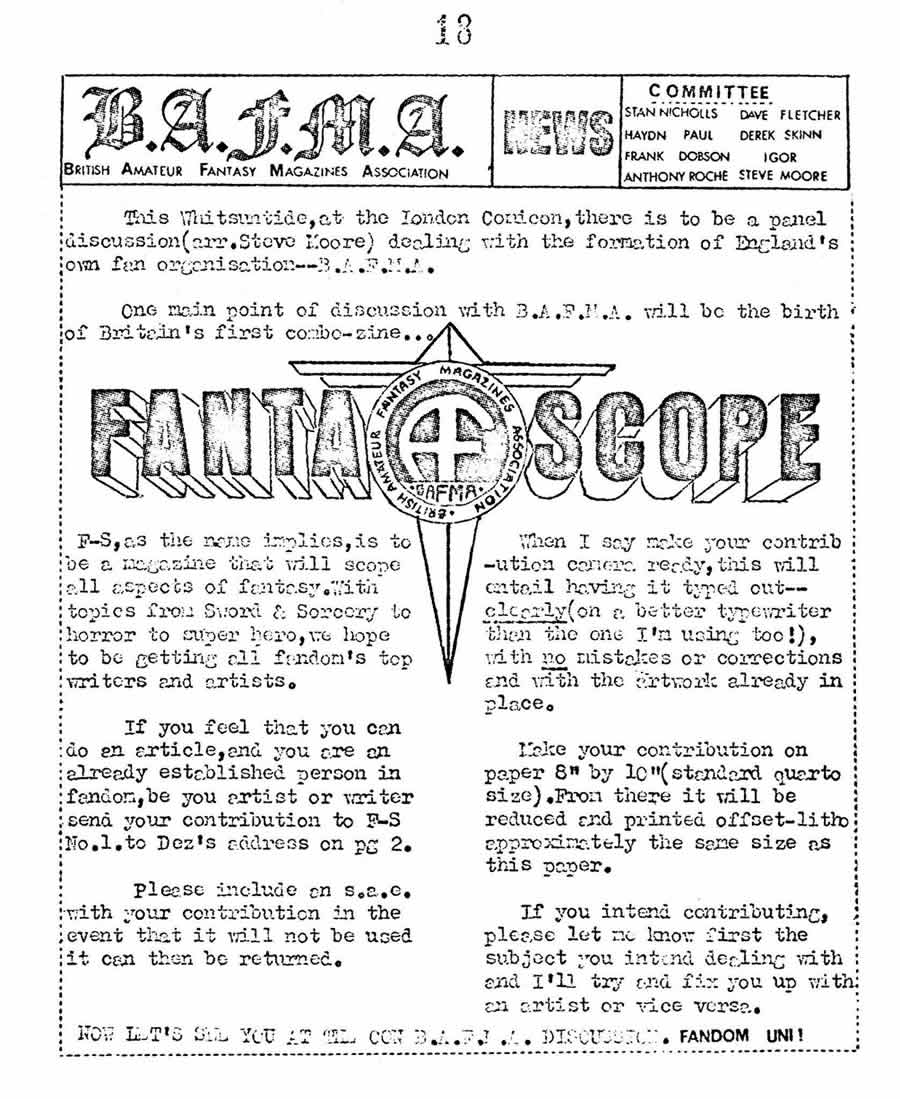

Here's another announcement, aimed at the nascent UK comics fandom and published somewhere I don't recall. I reckon it must be from 1972 or 73. Frankly, I don't remember very much about all this except that Fantascope, the proposed magazine, never happened. The British Amateur Fantasy Magazines Association (BAFMA), intended to represent the plethora of fanzines being published at that time and maybe gaining them wider distribution, never happened either, despite some impressive names on that committee, myself aside. Another might-have-been, I suppose.

FAVOURITE ARTISTS 9

Continuing the series I began here with the June 2023 update - scroll down for that - and which also runs on my Facebook page, here's the latest batch. Just two this month.

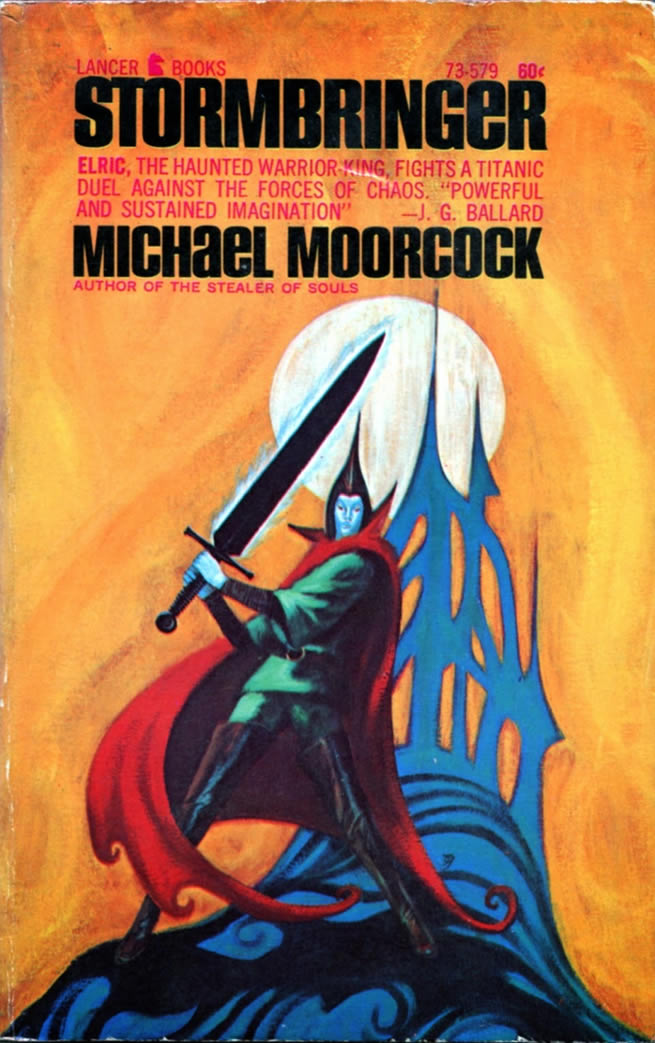

Favourite Artists # 30

JOHN BRIAN FRANCIS GAUGHAN (1930-1985).

The artwork here is from the cover of Galaxy magazine no 93 (vol 21, no 3), February 1963. The cover for Michael Moorcock's Stormbringer (Lancer Books, 1967) is below.

Jack Gaughan, his preferred working name, was a prolific contributor to both professional and fan publications. He made his first professional sale while still a student at the Dayton Art Institute, and in the1950s took up illustrating full-time. His covers and interior art appeared in Galaxy (where he was Art Editor for three years), If, The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction, Asimov's Science Fiction Magazine and a number of other titles. He also worked for book publishers, including Ace Books, Daw Books and Pyramid Books. Gaughan provided the covers for Ace Books' unauthorised editions of Tolkien's Lord of the Rings trilogy (1965).

A contributor of artwork to many fanzines throughout his career, he is the only illustrator to have won both Best Fan Artist and Best Professional Artist Hugo Awards in the same year (1967). He won the Best Professional Artist accolade again in 1968 and 1969. In his memory the New England Science Fiction Association established the Jack Gaughan Award, for best emerging sf illustrator.

Favourite Artists # 31

BRUCE PENNINGTON (b 1944).

The artwork here is from the cover of Gene Wolfe's The Shadow of the Torturer (Arrow 1981), and that for Clark Ashton Smith’s Lost Worlds Volume 2 (Panther 1975) is below.

Having trained at Beckenham School of Art and Bromley’s Ravensbourne College of Art, Bruce Pennington began gaining commercial art commissions in the mid-60’s. His association with the sf/fantasy fields took off in 1967 with his cover for Robert Heinlein’s Stranger in a Strange Land. Working for publishers including Ballantine Books, Corgi, New English Library and Sphere, he provided covers for books by Brian Aldiss, Poul Anderson, Harry Harrison, M. John Harrison and A.E. Van Vogt, among others. Perhaps his best known early cover was for the UK paperback edition of Frank Herbert’s Dune (NEL, 1968).

He’s had several compilations of his artwork published, principally Eschatus (1976), inspired by Nostradamus’ prophecies, and Ultraterranium (1991) both from Paper Tiger Books. A number of his illustrations have been used as album covers by various bands.

Since 1990 Pennington has concentrated on personal art and private commissions. His first exhibition was mounted at London’s Atlantis Bookshop in August 2011.

PHOTOGRAPH OF THE MONTH (62)

Herons are notorious for being easily spooked, and I was lucky to get reasonably close to this one on a cold February morning.

You can see all my Photographs of the Month, going back to January 2019, here.

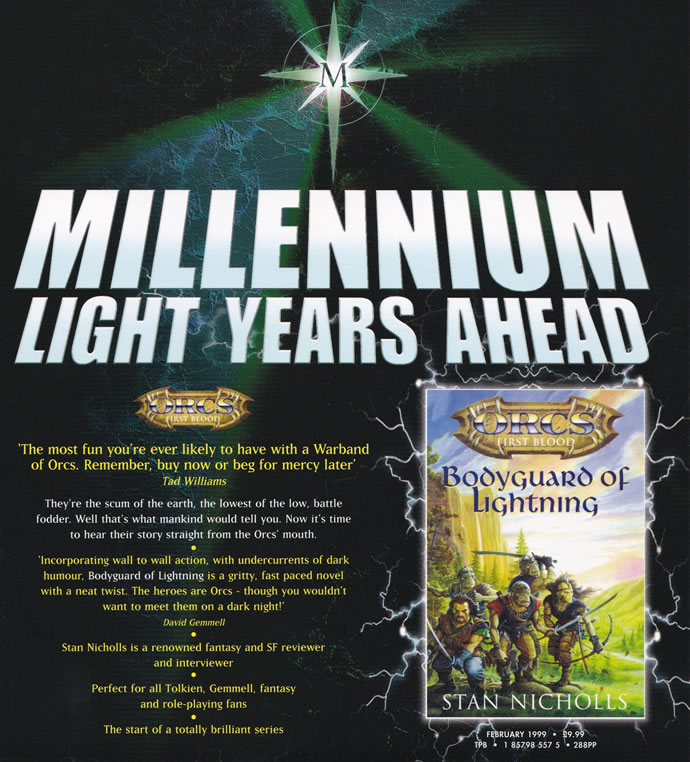

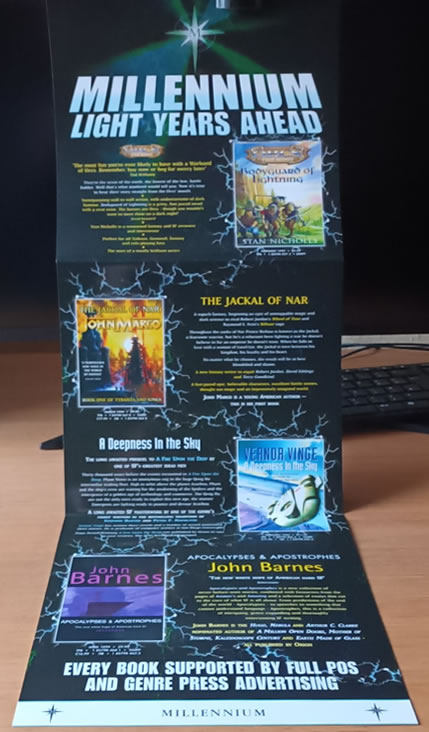

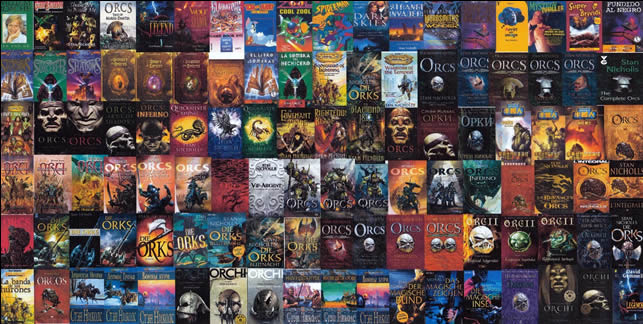

25 YEARS OF ORCING

In another of those startling realisations that time passes faster than a speeding bullet we've arrived at the 25th anniversary of the publication of the first book in my Orcs series. It was in February 1999, to be exact, when Bodyguard of Lightning, volume one of the Orcs: First Blood trilogy, saw the light of day. Here's the announcement from a trade catalogue my publisher put out at the time:

The publisher, The Orion Group, decided to launch a new sf/fantasy imprint, Millennium, with a raft of titles which, apart from mine, included books by John Marco, Venor Vinge, John Barnes, Darren O'Shaughnessy, James Lovegrove and Eric Brown. In the event, Orion bought the venerable publisher Gollancz shortly after and dropped the Millennium imprint. Bodyguard of Lightning was the only Orcs book to bear the Millennium logo; all the rest were published as from Gollancz. For the record, here's the back and front of that launch catalogue:

I'm proud of the fact that the initial trilogy achieved worldwide sales in excess of a million copies; and that it and the sequel trilogy, Orcs: Bad Blood, are still in print and continue to steadily sell. The series also spawned a collection, Orcs: Tales of Maras-Dantia (NewCon Press)and a graphic novel, Orcs: Forged For War (First Second Books), both of which are prequels. I've written quite a few non-Orcs books but I guess this series is what I'm perceived to be most closely associated with. I'm content with that and grateful for it.

There's an extensive section devoted to the Orcs series on this website. You can reach it via the above menu or directly here.

A BOOK PROMOTION MIGHT-HAVE-BEEN

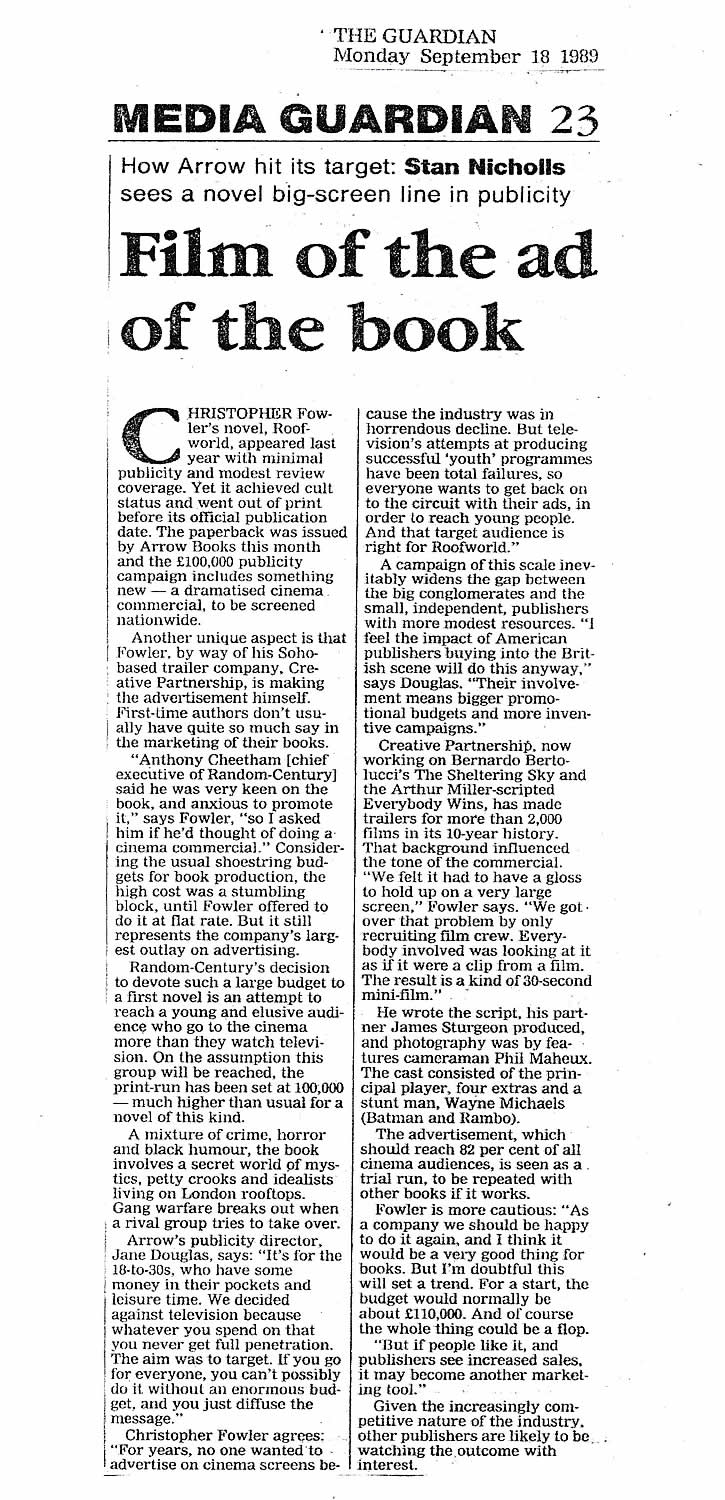

Trying to bring some kind of order to my clippings files, I came across this piece. As it centres on author Christopher Fowler, sadly lost to us in 2023, it seems appropriate to share it in his memory. When I wrote this the best we had was dial-up and the Internet was in its infancy – the information tsunami had yet to hit. It's interesting to imagine a timeline where it didn't and Chris' idea took hold.

FAVOURITE ARTISTS 8

Here are the next four of my Favourite Artists, a monthly series I began back in the June update (that you can see by scrolling down) and which also runs on my Facebook page.

Favourite Artists # 26

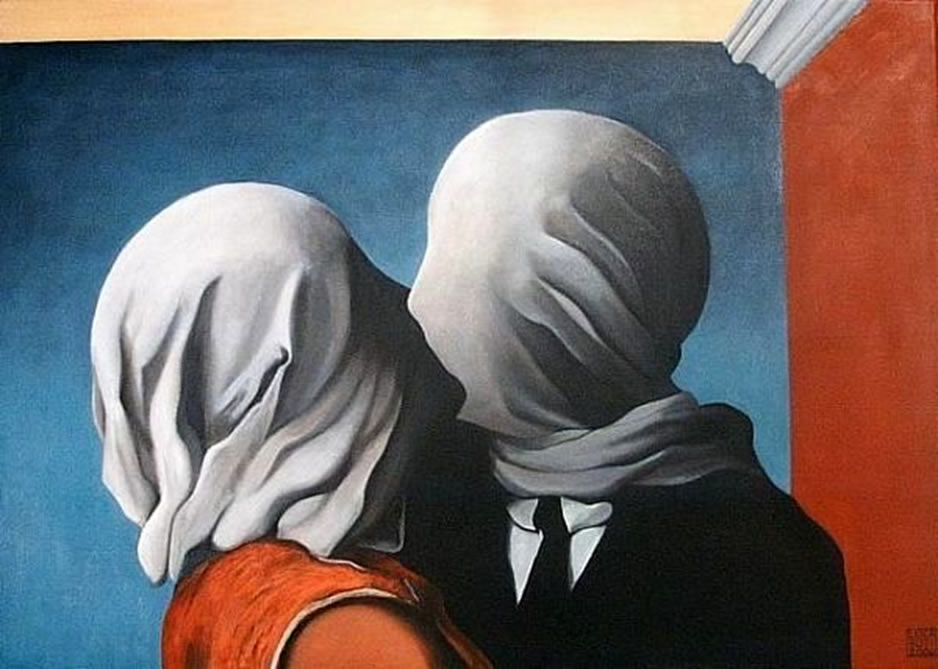

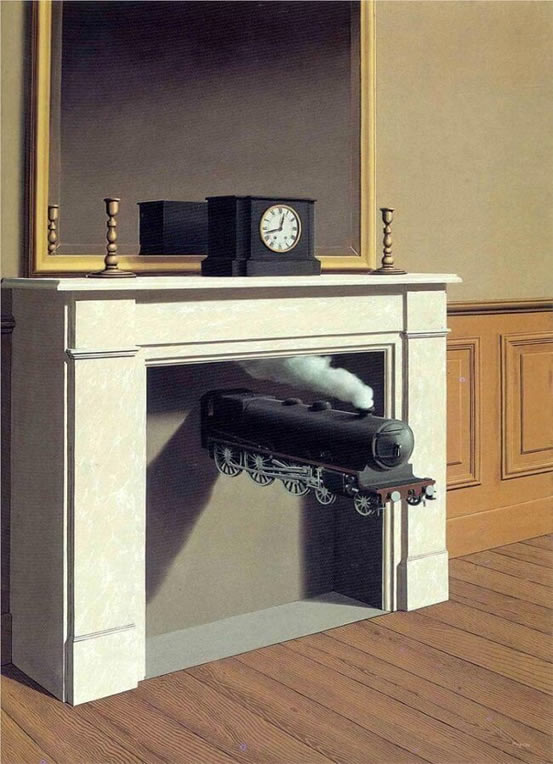

RENE (FRANCOIS GHISLAIN) MAGRITTE (1898-1967).

Principally associated with the surrealist movement, René Magritte was born in Lessines, part of Belgium's Hainaut province. Showing early talent, he began to take drawing lessons in 1910. In 1912 his mother, Régina, committed suicide by drowning, following several previous attempts. It's said that when her body was recovered her dress was covering her face, and there's a theory that this is why several of René's later paintings depict people with their faces obscured by cloth.

Magritte's earliest paintings, from around 1915, were in the Impressionism mode. Those he produced between roughly1918 and 1924 were inspired by Futurism and Cubism. Following just under a year's service in the Belgian infantry (1920-21) he worked as a draughtsman in a wallpaper factory, and also designed advertisements and posters.

1926 saw his first surrealist painting, Le jockey perdu ('The Lost Jockey'). His first solo exhibition took place in Brussels the next year and was badly received by critics. Deflated by that experience he moved to Paris, where he became friends with Andre Breton and was soon a leading member of the surrealist grouping.

Magritte stayed in Brussels during World War II's German occupation. In the austere years after the war he supported himself by producing fake works attributed to other artists, notably Picasso, and conspired with others, including fellow surrealist artist Marcel Marien, to print forged banknotes.

The painting here is The Lovers II. Another example of Magritte's work, Time Transfixed, is below.

Favourite Artists # 27

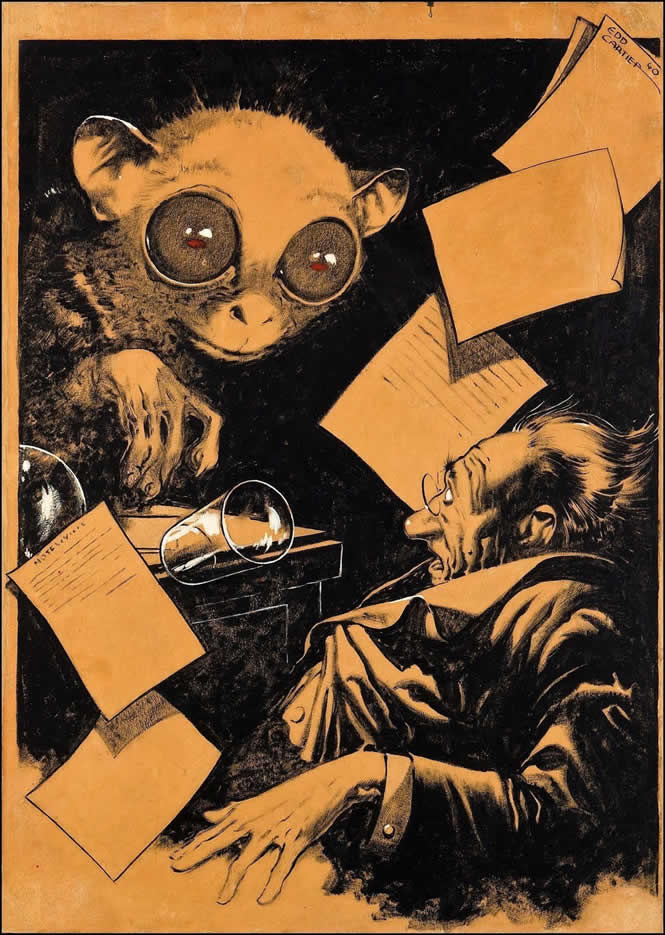

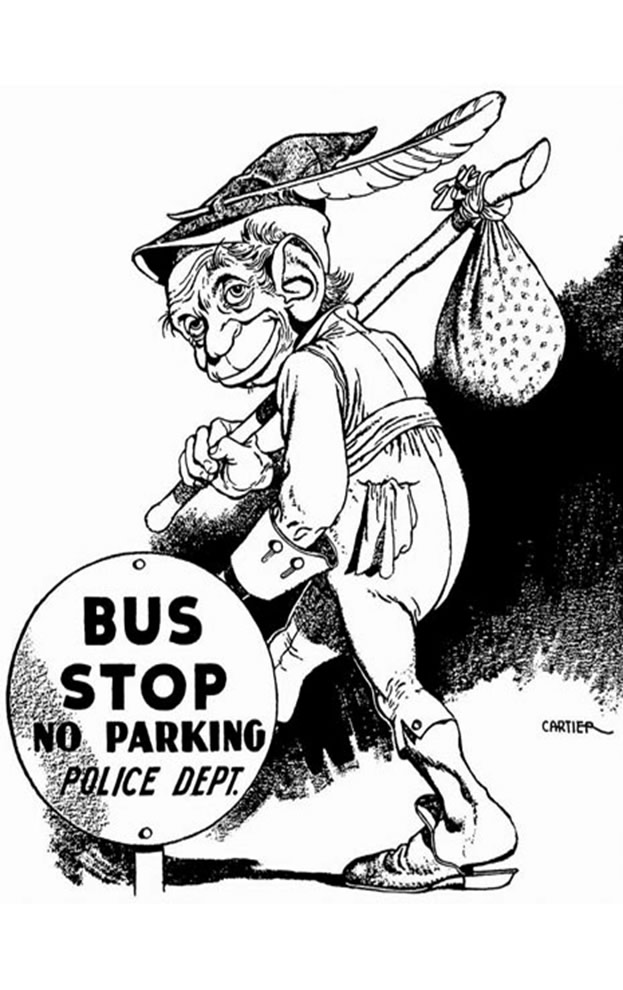

EDWARD DANIEL CARTIER (1914-2008).

Edd Cartier, as he was known professionally, was born in New Jersey and studied at Brooklyn's Pratt Institute. Following his graduation in 1936 he began contributing artwork to pulp magazines including Astounding Science Fiction, Unknown, Doc Savage Magazine, The Shadow, Planet Stories and Fantastic Adventures. Serving in World War II he was badly wounded during the Battle of the Bulge. Once recovered, and back in the United States, he returned to the Pratt Institute, earning a Bachelor of Fine Arts degree in 1953. He continued working for the pulps, principally Astounding, as well as Gnome Press and Fantasy Press.

As providing illustrations for pulps and small presses was lowly paid, Cartier found employment as a draughtsman with an engineering company, followed by 25 years working as Art Director for a New Jersey printing machinery manufacturer. He carried on producing artwork for magazines and book jackets on the side. Edd Cartier died at age 94 on Christmas Day 2008.

He was presented with a World Fantasy Lifetime Achievement Award in 1992.

The illustration here, from 1940, is pen and ink on board. An interior illustration from Unknown magazine is below.

Favourite Artists # 28

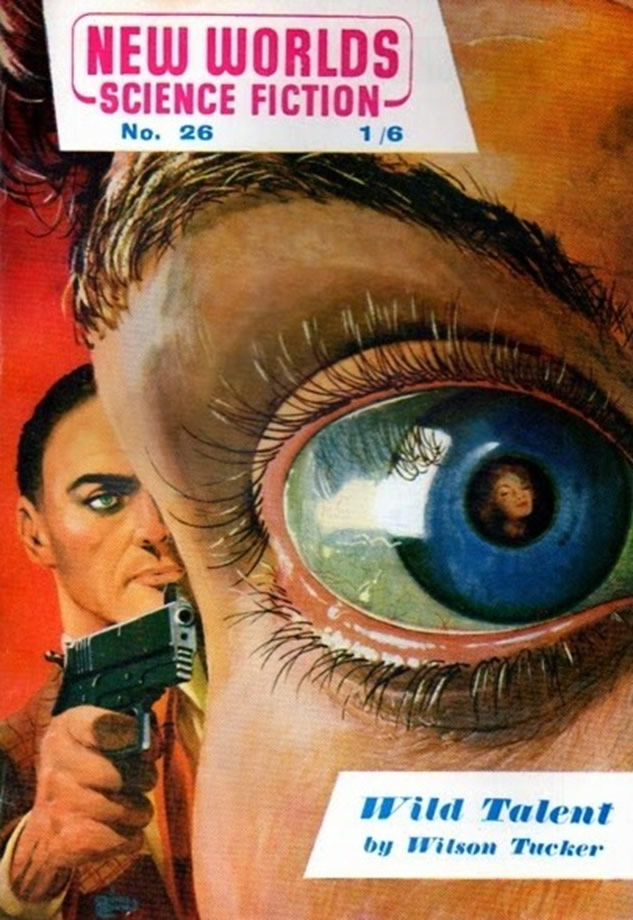

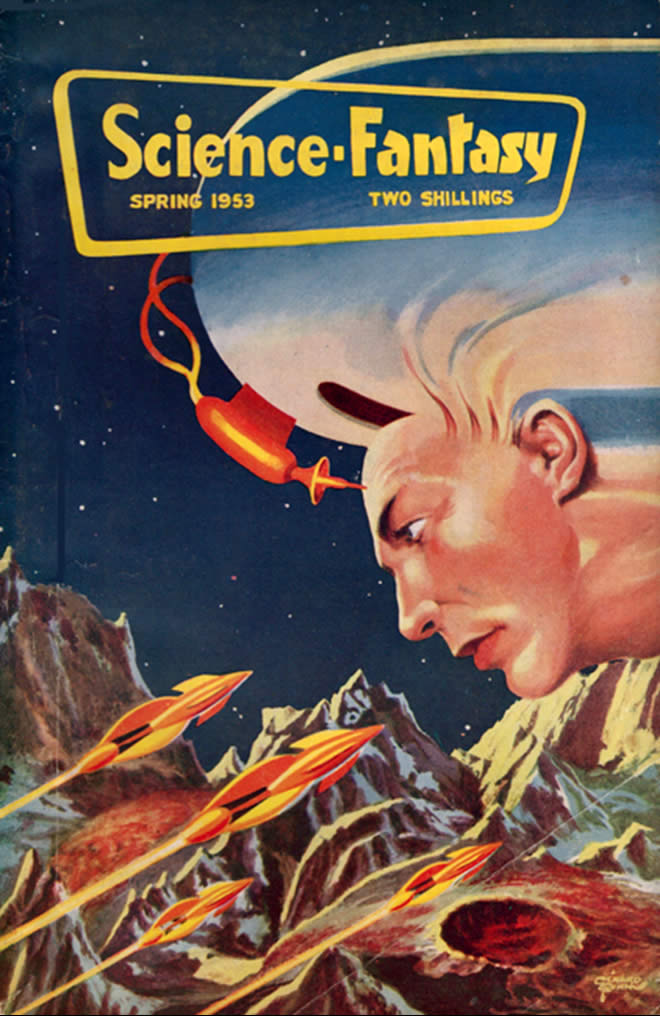

GERARD QUINN (1927-2015).

Belfast born Quinn was a prolific contributor of artwork to British science fiction magazines from the early 1950s to the 1970s. Self-taught, he broke into the field when he submitted samples of his artwork on spec to editor John Carnell, who commissioned interior illustrations and covers from Quinn for his magazines New Worlds and Science Fantasy. Between 1952 and 1963 Quinn supplied the cover art for more than 75 issues of the magazines, and books including titles by Arthur C Clarke and Robert Heinlein. Much later he provided several covers for the magazines Vision of Tomorrow and Extro. In common with other artists, Quinn found it difficult making a living in the sf field and in the 1970s moved into the advertising industry, working for several agencies until his retirement.

The illustration here is Gerard Quinn's cover for New Worlds number 26, August 1954. His cover for Science Fantasy number 6 (Spring 1953) is below.

Favourite Artists #29

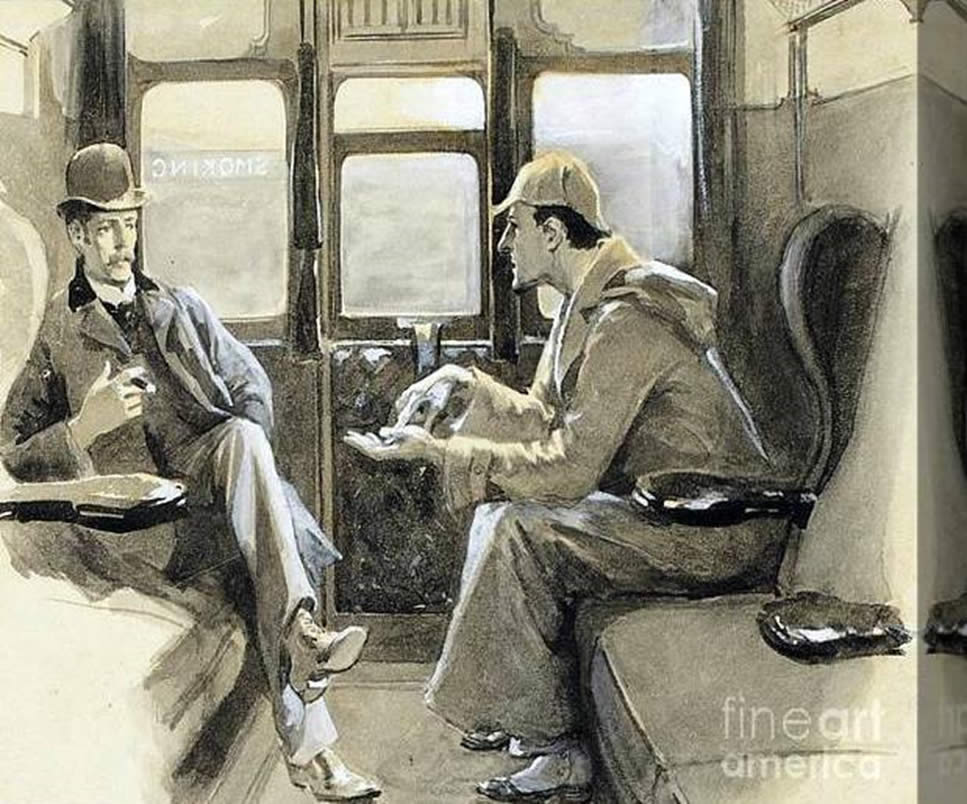

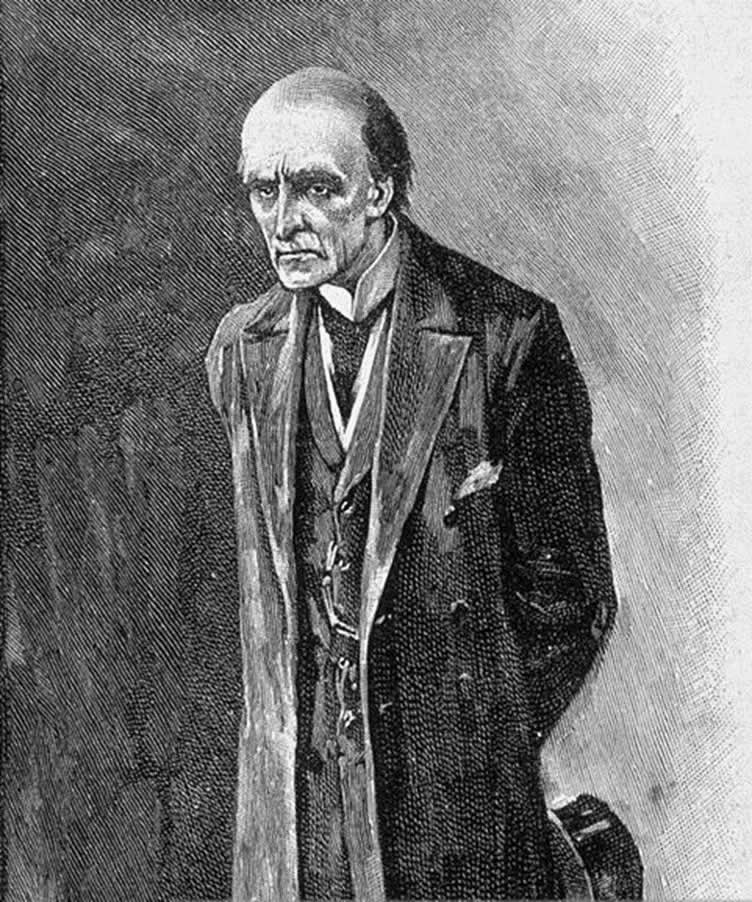

SIDNEY EDWARD PAGET (1860-1908).

Victorian artist Sidney Paget is best known for illustrating Conan Doyle's Sherlock Holmes stories in The Strand magazine. While studying at the Royal Academy of Arts he became friends with fellow student Alfred Morris Butler, who some scholars believe was the physical inspiration for Paget's later depiction of Dr Watson. Paget's interior illustrations appeared in The Illustrated London News, The Pall Mall Magazine, Pictorial World, The Graphic, The Sphere and famously, The Strand. He illustrated 37 Sherlock Holmes short stories and one of the Holmes novels, producing a total of 356 drawings. It was Paget who gave Holmes his deerstalker hat and Inverness cape, although neither are mentioned in any of Doyle's stories. His portrayal of Holmes has influenced how the character is depicted in literature, on stage and on screen to this day.

Paget developed a Mediastinal tumour, a rare condition that had no remedy in his day, and was only 47 when he died.

The illustration here is from the Sherlock Holmes story The Adventure of Silver Blaze (1892). Paget's portrait of Professor Moriarty, from The Final Problem (1893), is below.

PHOTOGRAPH OF THE MONTH (61)

In the not quite bleak mid-winter.

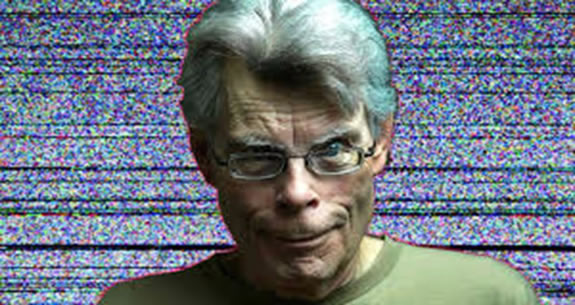

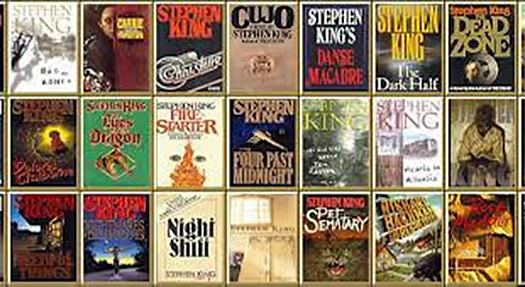

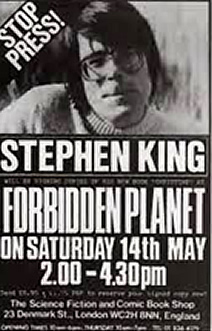

STEPHEN KING INTERVIEW

Time for another archive interview, this time with Stephen King, from SFX magazine number 45 (December 1998). There was a simultaneous online version on Line One (now TallkTalk), back when ISPs carried editorial content on their home pages; a truncated version in an American magazine, and a translation for a French publication. This is the definitive version.

The interview took place at Brown's hotel in London, which since its establishment in 1837 has been a favoured venue for artists and writers. Mark Twain and Agatha Christie often stayed, and frequent visitor Rudyard Kipling finished writing The Jungle Book there.King told me that he was thrilled the first time he sat at the actual desk Kipling used. A couple of days after conducting the interview, on 24th August, there was a launch party at the Royal College of Arms in Kensington Gore for Bag of Bones, the book he was in the UK to promote. The event included a rock 'n' roll set, with King on guitar. My wife Anne and myself were fortunate enough to be among the attendees.

I can't remember what title I gave the interview when I submitted it. In any event the magazine decided to change it, and I'll stick with theirs …

The Gospel According To Stephen

Even in these troubled times it's unusual for a celebrity to have a bodyguard present during an interview. However, Stephen King introduces his burly young minder as Joe. Joe seems friendly, but not the sort of man you would want to get on the wrong side of.

“He's here to look after me,” King explains in an easy manner.

In what way?

“He'll throw himself between us if you ask an inappropriate question.”

It was the kind of loquacious line you'd expect from one of the author's characters.

King's success transcends mere genre. Each of his 28 books have achieved multi-million sales, and the latest, Bag of Bones, hit the bestseller lists the day it was published. His work continues to be adapted for the screen at a furious pace. Currently, The Green Mile is being filmed with Tom Hanks, and a television mini-series penned by King, Storm of the Century, is also underway. Here's a writer whose income must resemble the gross national product of a medium-sized country.

It's hard to believe that this amiable, lanky 51 year-old, with his open, almost boyish face, needs a bodyguard. Then again, King wrote Misery, a tale of fan worship taken to the absolute extremes.

“Misery wasn't based on any kind of fan atrocity,” he says. “I didn't have too many of the real fanatics at that time. But I've picked up one or two since. There was a guy who broke into my house who claimed he had a bomb and would explode it if I didn't listen to his ideas. I wasn't there. I was in Philadelphia with my youngest son. My wife came down at six o'clock in the morning and this guy holds out a backpack and says, 'There's a bomb in here. I have to talk to Stephen King.' She ran out of the house in her nightgown to call the police. The bomb turned out to be pencils and erasers, and paper-clips that had been pulled apart into wires. In his mind, this was a bomb.”

Maniacs with phoney explosives aren't the only irritants he has to put up with. His wife once found a woman in their kitchen, going through the cupboards. 'I just wanted to see what he eats,' the stranger told her. 'Don't worry, I'm not crazy.' After these incidents security was beefed-up at the King's home in Maine, New England.

“Another extreme case is a guy called Stuart Lightfoot, who claims I was part of a conspiracy to kill John Lennon and it's provable through my works. He even believes I've confessed to it! He sends me passages of my own writing, and photographs of Mark Chapman, to whom I bear a faint resemblance.” At one point, Lightfoot set himself up in a caravan outside King's house. He claims King “stole his fame.” “He's nuts, that's all. He's like one of those guys you have standing on boxes here, at Speaker's Corner. One of the nutters in Hyde Park.”

Joe's muscular presence suddenly seems a little less unnecessary.

“But at the time I wrote Misery,” King reiterates, “I was only aware that there were a lot of people out there who read my books and who formed a connection to me through them in their own minds. It's totally untrue! I don't know these people, I don't have any relationship with them, and if we have anything in common it's our humanity.”

If the inspiration for Misery didn't come from a real life incident, where did the horrifying tale come from?

“Like the ideas for some of my other novels, that came to me in a dream. In fact, it happened when I was on Concorde, flying over here, to Brown's” Brown's of Mayfair, where this interview takes place, is one of London's most exclusive hotels. It's a perk of his tremendous good fortune, and a definite improvement on the second-rate motels he used at the beginning of his career.

“I fell asleep on the plane,” he recalls, “and dreamt about a woman who held a writer prisoner and killed him, skinned him, fed the remains to her pig and bound his novel in human skin. His skin, the writer's skin. I said to myself, 'I have to write this story.' Of course, the plot changed quite a bit in the telling. But I wrote the first 40 or 50 pages right on the landing here, between the ground floor and the first floor of the hotel.”

Indeed, the desk he sat at was the same often used by Rudyard Kipling when he stayed at Brown's.

“Another time,” King continues, “when I got road-blocked on my novel IT, I had a dream about leeches inside discarded refrigerators.” He smiles at the memory. “I immediately woke up and thought, 'This is where this is supposed to go.' Dreams are just another part of life. To me, it's like seeing something on the street you can use in your fiction. You take it and plug it right in. Writers are scavengers by nature.”

This could explain the line in Bag of Bones that goes, 'Perhaps in dreams everyone is a novelist.' The book features a writer, Mike Noonan, whose wife dies unexpectedly, which turns out to be a prelude to supernatural happenings. It's far from being the first time King has used an author as hero.

“I gave the manuscript of this book to my wife, Tabitha, and she rolled her eyes and said, 'Steve, it's another book about a writer.' And I said to her, 'When you get a new Dick Francis you don't roll your eyes and say, “Oh, another book about a jockey.”' She admitted it was true. Since writing's what I know about, it's a good place to go out from. But I also know about teaching, because I used to be a teacher, and I know about acting and the movie world and that sort of thing, so I can go to other places if I have to. Anyway, in a lot of respects Bag of Bones isn't so much about the world of writing as it is the world of publishing.” He grins mischievously. “The publishers love that part.”

Does he find it easier to write a narrative in first-person, as here?

“No, it's usually a little bit harder. Purely in a technical way, it's harder to get to all corners of the story when you're telling that story from the first-person perspective. It has its advantages, and it's the natural way people write to start with, but I think that for a novel it's a little more challenging, because you can't get to another place. You have to show how events work on the main character, because the reader can only see what he sees.”

In the book, Noonan admits that he finds it difficult to ask for help, or to express his feelings. Some would say that kind of buttoned-down attitude is very English. Is it very Stephen King?

“Yes, it is. It's me, it's very English, and you have to remember that when I write a book like Bag of Bones I'm writing about New England, where we're very close to our English forebears. Sometimes people ask, 'Why have your books been such a success in England?' and I'll say, 'Because I'm their people and they're my people and we're close.' So yeah, it's an English thing and a Yankee thing to say, 'I'm fine. I don't need any help.'”

Something else his hero says is that being paid to write is like having “a licence to steal.” Does he feel that way himself?

“Yes, I do. I think it's wonderful that they pay me and it's allowed me to send my kids to college. When I got married I had a teaching degree but I couldn't find a teaching job, so I went to work in an industrial laundry, washing motel sheets. It was probably 110, 120 degrees in there in the height of the summer and I got down to about 175 pounds. I was working 60 hours a week and making $1.75 an hour, barely enough to support my family. Now, I work maybe four hours a day, seven days a week, and that's still only 28 hours a week. I sit in an air-conditioned office and they pay me millions. It's a lot easier than, say, loading lorries at a warehouse out in Sheffield or somewhere. But it's the work I was made for and, of course, I'd do it for free if I didn't get paid.”

This is certainly true. He's a born writer. But as he currently earns advances of around $17million per book, it's unlikely to happen. He began writing seriously while holding down a day job, pounding out his work on a second-hand typewriter costing $35. He made his professional break in 1967 when he sold a short to Startling Mystery Stories. The payment amounted to a few cents a word. His career really took off with the publication of his debut novel, Carrie, in 1974, and Salem's Lot the following year. These days, he's said to be outsold only by the Bible and the Koran.

As he did it all with horror, often graphically described, the question has to be if there's anything he wouldn't write about, any taboo he wouldn't touch.

“It's a question I usually elect not to answer, because then somebody says, 'Well, what are those things which you choose not to write about?' But my feeling is that the more taboo the subject seems to be, the more it interests me to see whether or not I can write about it. I like the challenge of it and I like the danger of it. Take my novel The Dead Zone. If there's a taboo in the States, it's a great sensitivityto the idea of political assassinations. At the same time, there's a whole load of people in America who say that everybody should be able to own a gun if they want to, despite the fact that all the major assassinations were carried out with guns. Now, you can't get close enough to a president, or someone like Martin Luther King, to strangle them or stab them because somebody like Joe over there would step in and stop you.”

The ever-present Joe fidgets a bit and looks slightly uncomfortable.

“But if a guy's got a rifle he can take me out or take you out if he wants to. So what we've done is to try and create this taboo about using guns, and to present assassination as a cowardly act, something no sane person would do. I started to wonder 'Would there ever be justification for that sort of assassination, the man in a high place with a gun? Would you kill Hitler if you could go back in a time machine?' That was the starting point for The Dead Zone.”

King is aware that we're living through an age in which sticking your head above the parapet isn't always wise. This is touched on in Bag of Bones, where Noonan worries that onlookers might misunderstand his motives in trying to comfort a child in the street.

“Wasn't there a story in this country recently about teachers being warned not to put suntan lotion on kids?” King says. “I have a friend who teaches high school in my home town. He's probably 45, and he's done the job for a long time. I've seen teenage girls, his pupils, run to him and he'll give them a big hug. I said to him one time, 'Lenny, you're going to get into trouble if you do this.' His response was, 'Fuck 'em. The day I get into trouble for hugging a kid I'm out of this business, because that's part of what kids are about.'”

“Our generation is terrified of license because we grew up with everything. If you had a nickel for all those things the people in our generation have not told our kids we've tried: the drugs, the sex, the theft, the destruction of property … You've got a woman who is, let's say, 40 years old, who says to her teenage daughter, 'I don't want you out past 11 o'clock at night. You could get AIDS.' Or she'll say, 'What are you doing walking around in a tank top? Anybody can see your bra-straps.' What she's not telling the kid is that when she was 20 she had lice in her hair, she was hitch-hiking, fucking guys for rides between LA and Washington, because that was a different world. I think people from my generation have forgotten on a conscious level exactly what we were into and what we were up to. But on a deeper level it's still there, and it's come out in this really absurd Victorian response to sexuality. One of the motive forces behind Bag of Bones is that I've been married for 25 years, and I've been faithful to my wife, but I notice young girls much more than I used to, and I think a lot of people in my generation have so sublimated their own desires and their own feelings that they have these tendencies to see monsters everywhere. Monsters of sexuality, monsters from the id. We know what kind of trouble we got into with that behaviour. Maybe we don't always want to admit it to ourselves, but we know and we'd like to spare our kids that. I mean, isn't that part of being a parent? You want to spare your kids some of the bullshit you went through. What was fun at 20 seems tiresome at 40.”

He's written stories with vampires, werewolves and ghosts as the menaces, but for him real horror lies in everyday tragedy, like losing a wife or suffering writer's block, fates inflicted on the protagonist in Bag of Bones.

“They're terrifying thoughts in the way that cancer is a terrifying thought, where you say, 'I hope this doesn't happen to me, but it can't possibly happen to me because it's so terrible.' That's the denial that kicks in.“

He stops and asks, “Have you ever had writer's block?” I tell him yes, something approximating it, and it was very frightening. “Yeah, it's scary,” King agrees. “I had writer's block when I was in college. I was taking a lot of writing courses at that time and I believe writing is one of those things where the more you think about it, the harder it is to do. It's something you ought to do pretty much unregarded. But I don't worry about it a whole lot.”

Is it the old rule of “easy to read, hard to write” with him? Does he do lots of revisions? Does he sweat?

“I do a lot more than I used to and there are a number of reasons for that. The more success you have, the more people are watching what you do. I mean, people are really paying attention and that causes you to be self-conscious. But all that isn't really the way I was writing. I have always had a view that books are pre-existing things. I don't feel that I make stories up. I feel that I excavate them. I think that the job of the writer is like the job of the palaeontologist or the archaeologist. Here's this thing that's buried. Your job is to get it out as whole as you can. It's very fragile so you dig around it and you use your brushes or whatever as you try to get it out. It's there for you and you dig it up.”

How can a book pre-exist in that way? Does he mean in the sense that to a sculptor, a solid, unmarked slab of marble has a figure in it waiting to be unleashed?

“Yeah, that's right. For instance, people say to me, 'Where did you get the idea for Bag of Bones?' and I say, 'I don't know.' I was thinking one day about Rebecca, and about the gothic, and how the gothic is about secrets, about buried things. I guess at that point I had some sort of an idea that I was going to write a story about a man who's haunted by ghosts belonging to buried bodies on his property. Then at some further point I thought about a young woman being harassed by an old rich man who wanted custody of her child. But how those two things came together was like … “ He pauses to consider his words. This isn't easy for him to explain. “As I said, it was like archaeology. If there's a novel buried in the ground, so to speak, it's as though digging in one place brought up the base of a spine, digging in another revealed a skull. The actual excavation is an act of faith. You simply start at the beginning and assume that everything's there, and in this case everything was. But there was no outline, there was no plan, no road map of the plot. It kind of … revealed itself.” King laughs, the spell broken, a little embarrassed perhaps at revealing how the creative process works for him. He pushes a plate of biscuits our way. “Have a cookie.”

Joe doesn't take one. No doubt he likes to keep in shape in case he has to throw himself across his boss to save him.

We agree that there are one or two insightful critics. “Even three or four,” King amends. “My point is that occasionally someone will see something in the work that the authors themselves weren't aware they'd put in.” Has this happened to him, and did he ever take the credit when it did? “Yeah, that happens. I was at a writers' workshop where people were required to read something by me and then write a paper on it. The papers were presented while I sat at the back of the room and listened. Then I had to react to these papers, delver a kind of conversational critique, which puts the writer in a really uncomfortable position at times. Anyway, one guy critiqued my story Children of the Corn, about some people who fetch up in a small town in Nebraska where the children have murdered their parents on the orders of a heathen corn god. This guy did a long, really brilliantly executed paper saying this was all a parable about the American experience in Vietnam, and these children were symbolic Vietcong and the corn was the jungle and the interlopers were Americans and God, it never crossed my mind! I never thought once about Vietnam during the course of writing that story. While they were waiting for my comments, I'm thinking, 'This guy worked for weeks on this paper, he's got to get graded on it. All I have to do is open my mouth and say, “You're full of shit” and he's down in flames.' What I said was, 'Certainly the Vietnam war was a big part of my early life and there are a lot of things we draw from without even realising it, so this is probably a valid interpretation of the story.' But it wasn't.

“As for taking credit for that stuff, usually no. But, it's funny, sometimes the weirdest things happen when you write. For example, I wrote a story called Apt Pupil, which is about an American boy who's doing a research paper on the Holocaust, and he discovers this Nazi war criminal living on his block. It's about their relationship, because the boy's price for not turning this Nazi in is to hear about what went on in the camps and the extermination of the Jews. I gave this boy the name Tod Bowden, and my editor at that time said, 'This name is very clever.' I asked him what was clever about it and he said, 'Tod is German for death.' I said, 'Oh yes, of course it is.' I didn't know.”

Maybe it was something he picked up and stored subconsciously? “I'm not sure there really is a subconscious. I think the subconscious is a fairy tale for adults.” He doesn't subscribe to Freud's world-view? “Oh God, no!” Or Jung's? “No. Well … maybe. Sure, we get things passed on probably through our DNA, our chromosomes, but I believe our subconscious mind is a lot simpler and a lot cruder than Freud ever gave us credit for. It's basically as important, perhaps, as your gall-bladder, which you can have cut out and continue to live without very nicely. The idea of all this subconscious stuff is bullshit.”

What about race memory? “I believe in broad racial characteristics of thought and reaction, but they're very, very general. So general you could almost say they're part of the human metabolism. But race memory? No, I think it's probably romantic crap.”

On the subject of collective memory, I recall a scientist of some kind I heard on the radio a few weeks earlier. He was talking about why so many people are frightened of spiders, and his theory was that if you go back far enough in time spiders were a genuine threat to humans because they were much bigger. Like, the size of Alsatians. This strikes a chord. King pulls a face. “Spiders, I loathe them. I've heard another theory, and you'll love this: we have such a deep fear of spiders because they're actually extraterrestrials. They came here a long time ago on a meteor or something, and developed as a life-form. We understand instinctively that they're not from our planet.”

Uncomfortable a thought as this is for we arachnophobes, it's also somehow funny. I remind King that when Psycho was released Alfred Hitchcock said he couldn't understand why audiences found it so frightening. He regarded it as a comedy. Does King see any of his own work that way?

“Some of it, yes. My book Needful Things was meant to be a comedy. It was written very much with the Reagan administration in mind. I felt that Reagan was a kind of demon who came into town, the town in this case being America, and said 'You can have whatever you want. It's easy, anybody can do it. Junk bonds? Fine! Leverage buy-outs? Great! Cocaine? Fantastic! Whatever you want you can have it. All you have to pay with is your soul.' I guess a lot of people feel that way about the Thatcher regime here in England. I think that avarice and greed, any sort of sin of excess, is funny. I think acquisitiveness is funny. It just is, I'm sorry. What I'm talking about are crimes that we indulge in where we say to ourselves, 'We're really not hurting anybody, we're doing things for the best.' I mean, one of the problems Clinton's facing over the Lewinsky business is that he looks like a buffoon, doesn't he? Chasing after a woman who's 21 years old, who's basically not very interesting except for her physical attributes, reduces him to the level of a Punch cartoon. He looks like an elderly sugar daddy.” He doesn't buy the idea of a right-wing conspiracy then? “Good God, no. He's just a horny guy.”

Even Joe manages to crack a cautious smile at that one.

“There is an element of irony in the Clinton situation. I mean, for the first time since Kennedy we have a president who's young enough to have an interest in sexual matters. Kennedy certainly had a lot of affairs, apparently used his office in very much the same way as Clinton has used his, but in America there's a kind of unspoken rule of thumb: Republicans want your wallet and Democrats want your women. Those are the vices that they have. But anyway, I wrote this novel Needful Things, where a man comes to town and opens up a shop and basically trades for goods, and the trade always involves you doing some sort of a prank on one of your neighbours. Pretty soon the whole town is at war. Some nasty things happen in that book. There's a dog that's killed with a corkscrew, and there's a woman who's beaten to death, and a whole lot of other horrible stuff. But I say it's a comic novel. Certainly any story where a woman sells her soul to get Elvis Presley sunglasses you have to laugh about!

'Thing is, the book reviewed very badly because nobody saw it as a comedy. There's a mindset that comes into play with my work or with Hitchcock's work; we're seen a certain way. But anybody who pays attention to Hitchcock knows that he had a great black sense of humour.”

Many writers have little rituals, superstitions almost, they have to go through in order to start working. With Hemingway it was sharpening 24 pencils every morning. “Oh, I have them too,” King admits, “sure I do. And the rituals all serve the same purpose for the writer, which is to put him in the mood to write. It's like hypnotic trances. If you've never been hypnotised I've got to work to hypnotise you, but if I gave you certain triggers you can hypnotise yourself. You just have to go through a set ritual.

“With me, when I get up I want to have a glass of orange juice, and I want to have it where I can look at the newspaper. But mostly what I'm doing is just looking at the pictures. Then I have to put on the kettle, and it can't be on high heat, it can't be on low heat, it's got to be on medium heat because that way before the kettle whistles it's going to be 25 or 30 minutes, and by that point I'll be into what I'm doing. It's like going up on a ski lift – you wait until the hook comes along and then it catches you and you start up the slope. I also have to have one aspirin, and I was doing that long before I found out it was good for the heart. I take it because it's got caffeine. It's just a little accelerator to get you up that slope. It used to be nicotine for me. I was a heavy smoker before I finally gave it up.

“The writing implements I use don't matter too much. I like the word processor because it's fast.” Though he feels they have one important downside. “I used to do a draft with a typewriter or by hand and, you know what I'm talking about, this would be a big untidy stack of paper with coffee rings on it and I'd have stuff scribbled out and I'd have shit written between the lines. Now, with a word processor, the first draft looks like the finished draft. There are no strike-overs, there are no interlinings; it's all nice and neat and it looks great. But I have to remember it still needs to be rewritten. Fact is, I'm just as comfortable with a pen and a piece of paper.” A surprising number of his books, despite the fact that they can run to 500 pages and more, are written by hand.

“Mind you,” he tacks on, “I do have the perennial writer's fear, which is that I'll be found out. That the scales are going to fall from my publisher's eyes one day and they'll say, 'You fraud! We're paying you all this money and the emperor has no clothes on!'” He's joking. Mostly.

“What else frightens me? I've always thought clowns were scary. That's why I put one in IT. And I noticed, taking my kids to the circus, that they didn't want anything to do with them. They were terrified, my daughter in particular, because clowns are freakish, they're strange. Circuses are basically safe havens for the freakish and the weird. Those grotesque faces and that unending laughter is the kind of thing you find in a lunatic asylum. Even children understand that's not natural.”

In the publicity material accompanying Bag of Bones King refers to Shirley Jackson's The Haunting of Hill House. Jackson personifies the brand of fiction he finds the most unsettling.

“As far as the ghosts and vampires and so on go, we like that sort of thing because we know they're not true. They're very safe in a way. They're fun. But The haunting of Hill House is very, very upsetting to read. Jackson's book, and something like James' The Turn of the Screw, are upsetting to us for a couple of reasons. One is because we don't know how much of it is an actual supernatural phenomenon, and if it is a supernatural phenomenon it's still terrifying because those ghosts are not friendly. The other possibility is that we're watching the workings of a mind that's not sane any longer, and that's disturbing too.

“I love Shirley Jackson. She's the best. I'd like to think that my fiction could be as affecting. Over the course of the years you get to know when you've written something that seems to work; when you've got that thing out of the ground pretty much intact. I feel like I did that with Bag of Bones. I love the book. Also, I've been doing this job for 25 years now, and a lot of people who are reviewing me grew up reading my stuff and I'm getting the benefit of that. You get good critical comments if you've done the job well. But you also get points for still being alive, like Bob Dylan or Pete Townsend.”

It's time to go. I leave him pondering his longevity, nod to Joe and make my way out. I calculate that at least a couple of thousand more Stephen King books have been sold in the time we were talking.

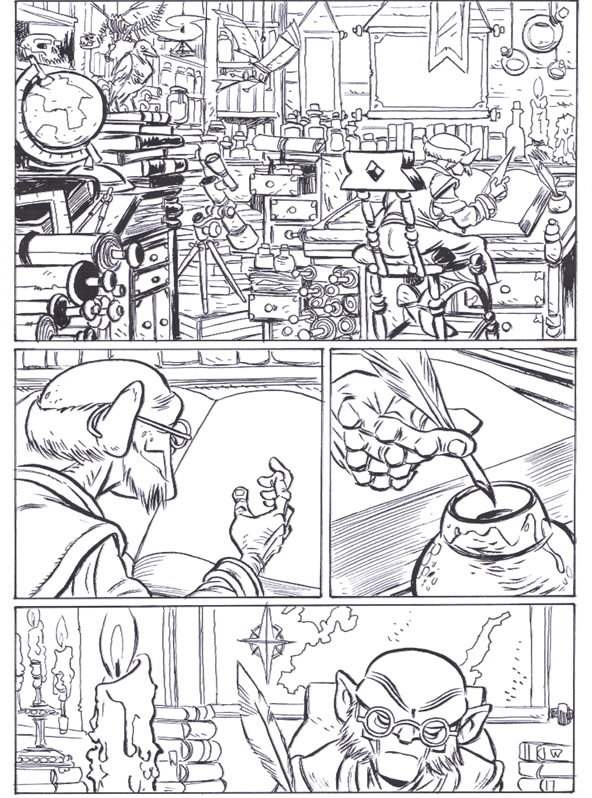

REDISCOVERED ARTWORK

A further delve into the archives has turned up a page of forgotten artwork. Many projects evolve and develop in the making, and in my experience this is particularly true of any book dependent on artwork, like graphic novels. The graphic novel Orcs: Forged For War (First Second Books), which I created with artist Joe Flood, is no exception. The intention was to have an introduction in which an elderly scholar begins to recount the story that followed. Joe inked the pages, but before they went to the colouring stage it was decided to drop that section as we were close to the page limit and, to be honest, an intro wasn't really necessary to advance the plot. Here's the first page Joe produced:

FAVOURITE ARTISTS 7

The series featuring some of my favourite artists which I began posting here with the June update usually includes four choices per month. But as this update is somewhat longer than usual I thought I'd feature just one and return to four next time.

Favourite Artists # 25

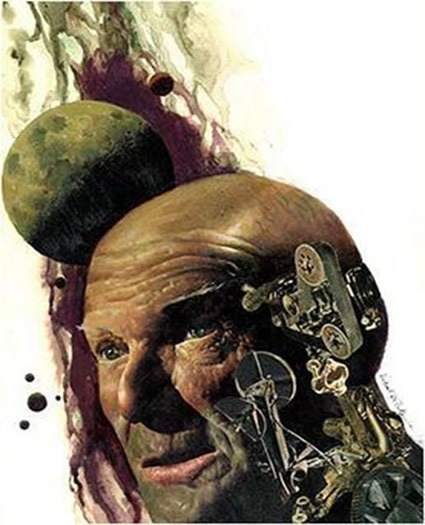

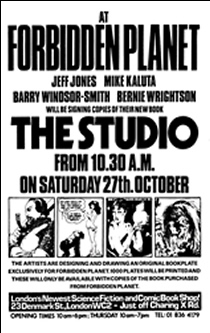

DIDIER GRAFFET (b 1970).

A graduate of École Émile Cohl, the educational institution in Lyon, Didier Graffet began his career as a freelance illustrator in 1994. He has produced many fantasy fiction book covers for French publishers. In 2001 he illustrated an edition of Jules Verne's Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea, which earned him the Grand Prix de I'Imaginaire Award and Jules Verne Award. His illustrations for Verne's Mysterious Island (2005) were equally well received. He subsequently worked for the Jules Verne Adventures Studio, creating posters for its festivals in Paris and Los Angeles, and is currently acting as Artistic Director on a documentary film with the organisation. Apart from fantasy and Verne devotees, his work has found particular favour with Steampunk enthusiasts, and has been widely exhibited in galleries and other venues.

The piece here is entitled Astoria. The example below is Le jour du chasseur (The Day of the Hunter).

Disclosure: Didier produced sixteen covers for French editions of my books. But that isn't why I've included him in this series – I like his work regardless.

PHOTOGRAPH OF THE MONTH (60)

This is often how we'd like December to be, but in this era of climate change the weather doesn't always cooperate.

I regularly post photographs on my Facebook page; and all previous Photographs of the Month featured here can be found in the Photo Gallery.

… to all who celebrate Christmas, and a happy and peaceful New Year to everyone.

Ed Emshwiller was number 9 in my Favourite Artists series. This is his cover artwork for the December 1954 issue of Galaxy magazine.

FAVOURITE ARTISTS 6

Here are the next four of my Favourite Artists, a monthly series I began back in the June update (which you can see by scrolling down).

Favourite Artists # 21

VINCENT DI FATE (b 1945).

New York born science fiction and fantasy artist Di Fate broke into the magazine market with interior illustrations for the August 1969 issue of Analog, followed by his first cover for the title in November of that year. He has a Master of Arts degree in Illustration from Syracuse University, and has produced astronomical and aerospace themed art for clients including IBM, NASA, the National Geographic Society and Scientific American magazine. The Disney corporation, MCA , MGM and several other media companies have employed him as a consultant.

Vincent Di Fate's many awards include a Hugo for Best Professional Artist (1979), the Edward E Smith Memorial Award (the Skylark Award) in 1987 and the Chesley Award in 1998. He was inducted into the Science Fiction Hall of Fame in 2011.

The first illustration here is 'Ares and the End of All.' The cover art for Ron Goulart's short story collection Broke Down Engine (1969) is the second.

Favourite Artists # 22

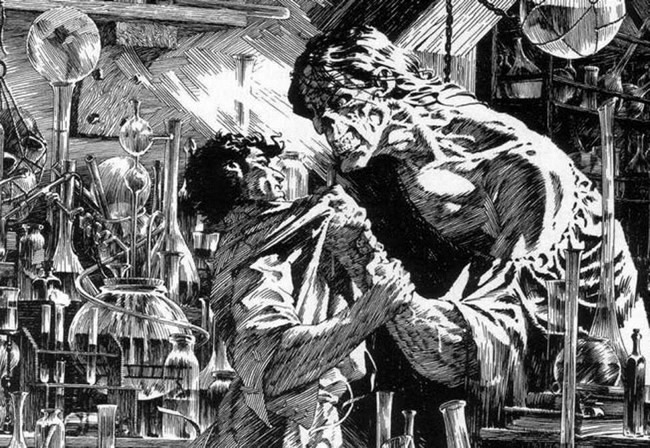

BERNARD ALBERT WRIGHTSON (1948-2017).

Bernie Wrightson began his career as an illustrator for The Baltimore Sun newspaper in 1966. A meeting with Frank Frazetta (number 18 in this Favourite Artists series) at a comics convention the following year inspired Wrightson to pitch his portfolio to DC Comics. That led to regular work on DC's stable of supernatural anthology titles, notably House of Mystery and House of Secrets. He later also freelanced for Marvel's similarly themed Chamber of Darkness and Tower of Shadows.

In 1971 Wrightson and writer Len Wein created the popular Swamp Thing character for DC. 1974 saw him working for Warren Publishing's Creepy and Eerie horror titles, and later, collaborations with Stephen King on several comicbook adaptations of King's novels.

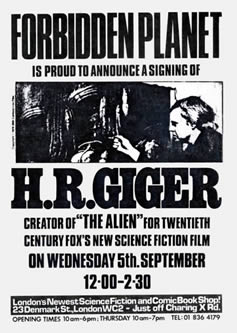

In 1975 Wrightson joined with fellow artists Jeff Jones, Michael Kaluta and Barry Windsor-Smith to form an art collective called The Studio. The quartet shared a loft studio in Manhattan working on projects that left behind the sometimes notorious restrictions of the comicbook industry. The project that many consider Wrightson's masterwork, an illustrated edition of Mary Shelley's Frankenstein, which took him several years to complete, was published in 1983. In his later years he acted as a film and TV concept artist.

The second image below is a detail from one of Wrightson's Frankenstein illustrations.

Favourite Artists # 23

GERRIT DOU (aka Gerald Douw or Gerald Dow; 1613-1675).

Dutch Golden Age painter Gerrit Dou was born in Leiden. His father manufactured stained glass, and Gerrit was trained in the same trade at the workshop of one of his father's associates. At the age of 14, in 1628, Gerrit was sent to study painting in the studio of Rembrandt, who was only 21 himself at that time and lived nearby. Dou's three years there saw him develop a style that reflected Rembrandt's, but he soon formulated his own approach, which differed greatly from his one time master's. His working methods were elaborate and painstaking - he's reputed to have once spent five days painting a hand - and his work was so fine, typically on quite small canvasses, that he had to manufacture his own brushes.

The painting here is 'Sleeping Dog' (1650). 'Scholar Sharpening a Quill,' thought to have been painted some time between 1630 and 1635, is below.

Favourite Artists # 24

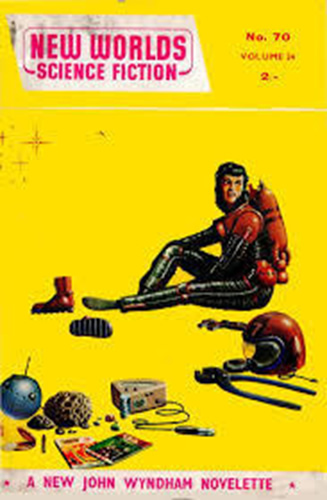

BRIAN (MONCRIEFF) LEWIS (1929-1978).

Brian Lewis' career as an illustrator began after serving in the RAF. Some of his earliest work was for the Nova magazines New Worlds, Science Fantasy and Science Fiction Adventures, to which he contributed a total of around eighty covers. In the late '50s he moved into British comics, drawing strips for Tiger, Eagle, Boy's World, Wham!, Smash, Buster and several others.

In the '60s and '70s he was active in adapting TV series to comic strips for Countdown,

TV 21 and TV Action. During this period he also moved into animation, notably on the Beatles' film Yellow Submarine. His other credits included work for 2000 AD, House of Hammer and Warren Publishing's Vampirella.

Suffering from a heart condition, Brian Lewis was only 49 when he died.

The illustration here is from the cover of New Worlds number 70, April 1958, along with the complete cover. Below that is one of Lewis’ illustrations from Cinderland, an adaptation of the Cinderella story.

PHOTOGRAPH OF THE MONTH (59)

Autumn colour.

FAVOURITE ARTISTS 5

Here's a continuation of my personal list of Favourite Artists, which I began in the June update (scroll down to see).

Favourite Artists # 17

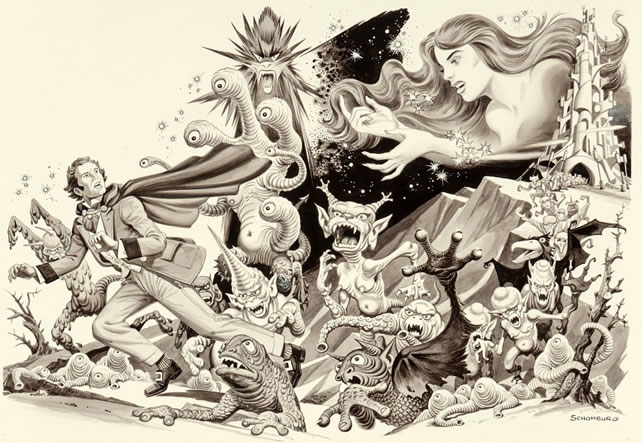

ALEX SCHOMBURG (born Alejandro Schomburg y Rosa; 1905-1998).

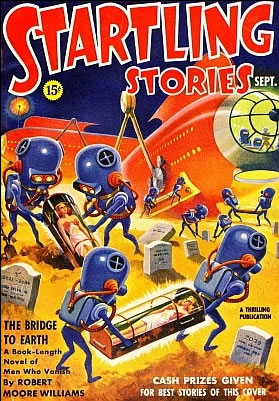

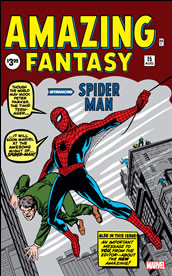

Puerto Rica-born Schomburg enjoyed a prolific seventy year career producing covers, and some interior illustrations, for comics, pulp/digest magazines and books. Having moved to New York in 1917 he began working as a commercial artist in 1923. In the 1930s he moved on to pulp covers for titles including Thrilling Wonder Stories and Flying Aces.

The 1940s saw Schomburg providing many covers for Timely Comics (the forerunner of Marvel) featuring popular characters such as Captain America, the Human Torch and the Sub-Mariner. He also worked for rival companies illustrating the covers of comics centring on superheroes the Black Terror, the Fighting Yank and the Green Hornet, among others. He continued working well into his senior years, and garnered many awards in both the comics and science fiction fields. He was inducted into the Will Eisner Hall of Fame in 1999.

The artwork here is entitled 'Dear Caressa or This Towering Torment'. (Inkwash on board.) His first cover for a science fiction pulp, the September 1939 issue of Startling Stories, is below.

Favourite Artists # 18

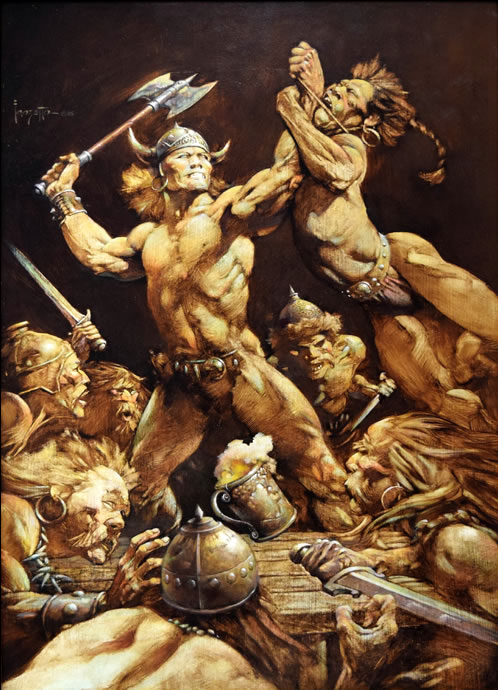

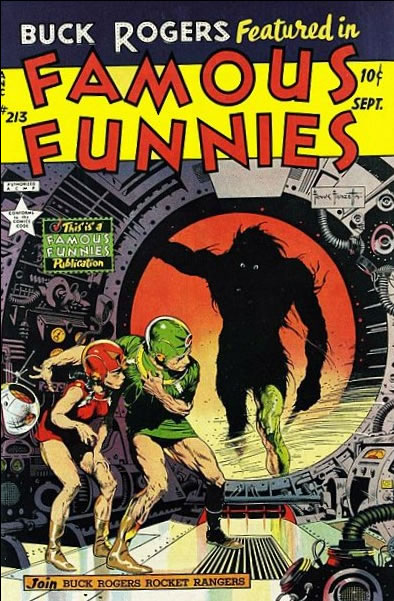

FRANK FRAZETTA (born Frank Frazzetta;1928-2010).

Putting aside any issues about his generation's tendency for objectification – curvaceous women absurdly going to war or into space wearing gold lame bikinis and the like (no doubt delighting hormonal teenagers when they first discovered the genre) - I couldn't fail to include arguably the 20th Century's greatest fantasy/science fiction artist. Frazetta really was in a class of his own.

Displaying a talent for art from childhood, he got into the comics industry when he was just 16, in 1944. And around that time he dropped one z from his surname, which he declared was “clumsy” with two. Frazetta worked extensively in comics until around 1952, although given the business' refusal to credit creators at that time it's difficult to identify everything he did. After a spell working on newspaper strips he returned to comics in 1961, and also contributed to Harvey Kurtzman and Will Elder's ribald 'Little Annie Fanny' strip in Playboy magazine.

In the mid-'60s he was commissioned to produce the poster for the Woody Allen film What's New Pussycat/? which led to a supplementary career illustrating movie posters. He also got into book covers, notably oil paintings for the Lancer Books editions of Robert E Howard's 'Conan' series, which proved enormously popular and influential. Although ironically, as he later admitted, "I didn't read any of it... I drew him my way.” Additionally, in this highly productive period he contributed covers and some interior stories to the Warren magazines Creepy, Eerie, Vampirella and Blazing Combat.

The 1980s saw Frazetta establish a gallery, Frazetta's Fantasy Corner, in Pennsylvania, exhibiting both his own work and that of other artists. His many accolades included being inducted into the Will Eisner, Jack Kirby, Society of Illustrators and Science Fiction Halls of Fame. In June 2023 his painting 'Dark Kingdom' was auctioned for $6million, setting a

record for the most valuable work of fantasy art and breaking the record of the previous holder, Frazetta's 'Egyptian Queen' (£5.4million).

The artwork here is 'The Disagreement' (1985) and below is the cover for Famous Funnies no 213, September 1954.

Favourite Artists # 19

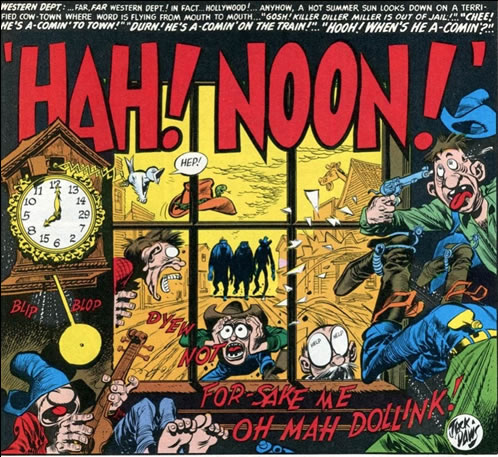

JACK DAVIS (John Burton Davis Jr; 1924-2016).

Cartoonist and illustrator Jack Davis was first published at age 12 when he had a cartoon accepted for issue 9 of Tip Top Comics in 1936. Following three years in the US Navy during wartime he found work with EC Comics, contributing covers and strips to Tales From the Crypt, The Vault of Horror, The Haunt of Fear, Two-Fisted Tales, and Frontline Combat among others. He was one of the founding artists of Mad magazine in 1952, and was a long-term mainstay of the title.

Davis produced the poster for comedy western Viva Max! in 1969, and went on to create a number of other movie posters, including Kelly's Heroes (1970) and the 1973 adaptation of Raymond Chandler's The Long Goodbye. He illustrated music and comedy album covers for performers including Johnny Cash, The Guess Who, Bob & Ray, Sheb Wooley and Archie Campbell.

He received a Lifetime Achievement Award from the National Cartoonists Society in 1996 and was inducted into the Will Eisner Hall of Fame in 2003.

The Jack Davis illustration here is from the cover of EC's Incredible Science Fiction no 31 (September 1955). The opening panel from his parody of the film 'High Noon' from Mad magazine no 9 (March 1954) is below.

Favourite Artists # 20

PIETER CLAESZ (c1597-1660).

Dutch Golden Age artist Pieter Ciaesz was one of that era's leading painters of still life subjects. Born near Antwerp, Belgium, he moved to Haarlem in 1620, where his son Nicolaes Pieterszoon Berchem, later a noted landscape artist in his own right, was born. Much of Claesz's work was characterised by a subtle, almost subdued choice of colours, although his later canvases employed a more colourful palette.

The work here is 'Still Life with Turkey Pie' (1627). Below is 'Still Life with Skull and Candle' (1625) . Claesz had a thing about skulls. He used them as a metaphor regarding mortality.

PHOTOGRAPH OF THE MONTH (58)

An October dawn.

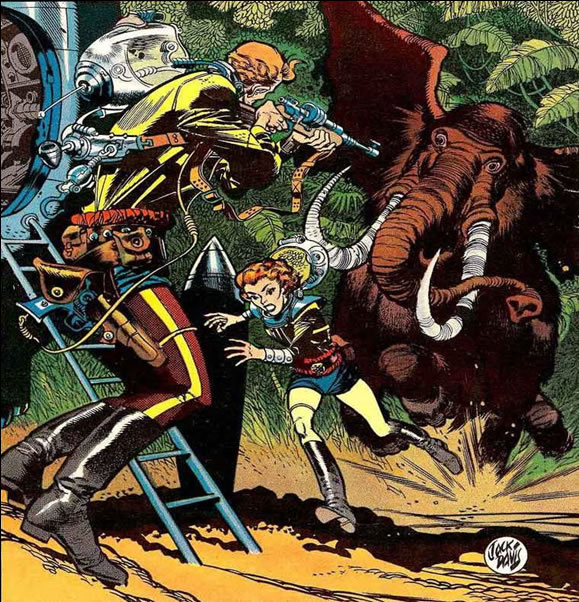

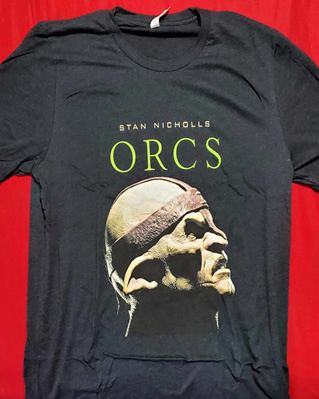

WEARING MY BOOKS

A shout out to my friend Sky Campbell, who's utilised one of my US book covers on t-shirts, vests and other cool fashion items.

Sky's a software and games developer, and until a couple of years ago was the Language Director for the Otoe-Missouria tribe of indigenous Americans in Oklahoma. He also very ably acted as the IT/Website Manager for the David Gemmell Awards for Fantasy (see the Photo Gallery here). I really do have some great readers, and I'm so grateful for them.

FAVOURITE ARTISTS 4

Continuing the listing I began with the June update (which you can see if you scroll down this page) here's the next batch of my personal Favourite Artists.

Favourite Artists # 13

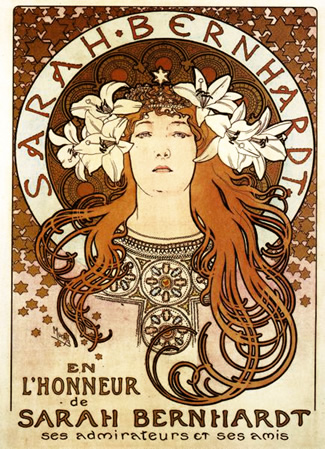

ALFONS MARIA MUCHA (known as Alphonse Mucha,1860-1939).

Czech-born Mucha was a painter and graphic artist whose theatrical posters, advertisements, book illustrations and jewellery designs were a major component of the

Art Nouveau movement. A gifted artist from childhood, at age nineteen Mucha left his native Moravia and travelled to Vienna, where he was employed as an apprentice scenery painter. During this period he became interested in photography, a tool he would use in his later work. In 1881 a fire destroyed the theatre of the scenery painting company's major client, leaving Mucha unemployed. He earned a modest income for the next four years by painting portraits, decorative art, and lettering for tombstones. Subsequently resident in Munich, he studied briefly at the Munich Academy.

He moved to Paris in 1887, and in 1894 his work drew the attention of famed French actress Sarah Bernhardt, who commissioned a theatre poster by him. His association with Bernhardt, and the quality of the series of posters he produced for her, saw Mucha gain many commissions for advertising posters, and art lecture engagements in the United States. His work also featured prominently in the Paris Exposition of 1900, the first high profile exhibition of Art Nouveau. Mucha died of pneumonia on 14th July 1939, less than two months before the outbreak of the Second World War.

Favourite Artists # 14

ALEX(ANDER GILLESPIE) RAYMOND (1909-1956).

Alex Raymond, “the artist's artist” in the estimation of many fellow cartoonists and fans, displayed an early talent for drawing. He found employment as an assistant illustrator on several newspaper strips in the early 1930s. In 1933 he created the enormously influential Flash Gordon comic strip in competition with the market-leading Buck Rogers strip, and soon overtook 'Buck' in popularity. Raymond also worked on adventure strip Jungle Jim and spy strip Secret Agent X-9, created by crime writer Dashiell Hammett. After a spell in the marines from 1944 to 1946 Raymond returned to his career, creating and illustrating private eye strip Rip Kirby. All these strips are considered milestones in the history of comic art. Many artists named Raymond as a major inspiration, including Batman co-creator Bob Kane, Jack Kirby and Al Williamson (number 5 in this Favourite Artists series). George Lucas cited Raymond as an influence on Star Wars.

On 6th September 1956, in Westport, Connecticut, Raymond was driving fellow cartoonist Stan Drake in Drake's Corvette at twice the speed limit when the car struck a tree and he was killed. Drake was thrown clear and survived. Controversy surrounded the accident. Drake and several others who knew Raymond believed that he was suicidal due to problems with his marriage, and pointed to the fact that he had been involved in four automobile accidents in the month leading to his death. “[he] had been trying to kill himself,” Drake claimed. Many other friends and acquaintances of Raymond dismissed the idea.

Raymond was inducted into both the Will Eisner Comic Book Hall of Fame (1996), and the Society of Illustrators Hall of Fame (2014).

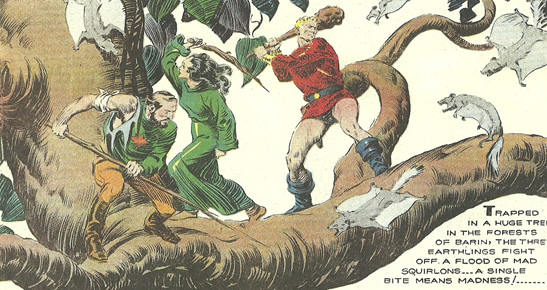

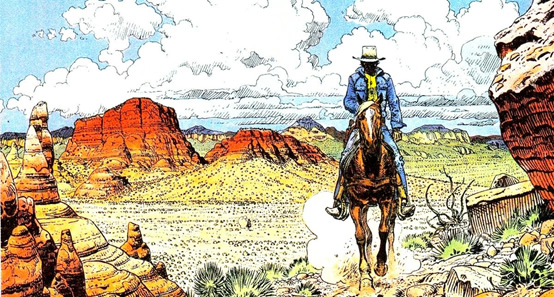

Favourite Artists # 15

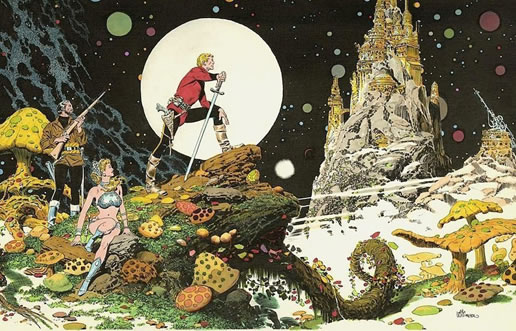

JEAN HENRI GASTON GIRAUD (known as Moebius and as Gir; 1938-2012).

French artist, writer and publisher Giraud was both enormously prolific and a major influence on other artists, film-makers and creatives in visual industries such as gaming. His somewhat surreal science fiction and fantasy works, as Moebius, and western stories as by Gir, principally the Blueberry series, won him international plaudits. He also produced storyboards and concept designs for a number of sf films, including Alien, The Fifth Element, Tron, Willow and The Abyss. The use of his work, too extensive to list here, extended from comics/graphic novels to album covers, film posters, trading cards, video games covers, calendars, limited edition prints and many other formats.

Displaying a talent for illustration from an early age, in 1956 he quit art school without graduating and spent time with his mother, who was resident in Mexico. The Mexican terrain, its deserts and plains, the quality of its light, had a profound effect on Giraud and featured widely in his work thereafter.

In 1988 Giraud illustrated a two issue Silver Surfer story, Silver Surfer: Parable, penned by Stan Lee, for Marvel's Epic Comics imprint. The miniseries won an Eisner Award, and more work for both Marvel and DC resulted.

Toward the end of his life Giraud's eyesight began to fail, and he underwent surgery in 2010 to prevent blindness in his left eye. Finding it increasingly difficult to work on comics and graphic novels, in his final years he concentrated on single image works on large canvasses, usually commissioned.

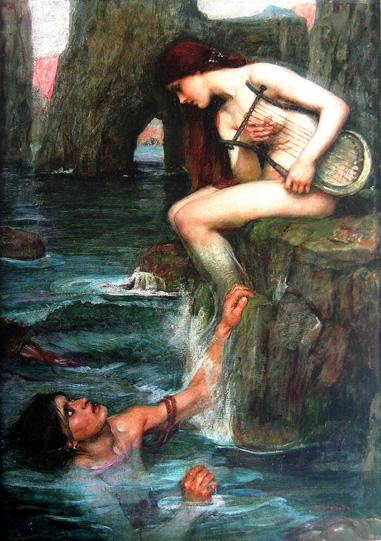

Favourite Artists # 16

JOHN WILLIAM WATERHOUSE (1849-1917).

After initially working in the Academic style, depicting scenes from Greek and Arthurian mythology, and Orientalist subjects, Waterhouse was drawn to the Pre-Raphaelites and became a major figure in the movement. Born in Rome to English parents, both artists, his early years in Italy are said to be the reason why the subject of many of his later paintings was Roman mythology. When Waterhouse moved to London he entered the Royal Academy of Art and was soon exhibiting at the Academy's Summer exhibitions. Throughout his career a number of his paintings were based on the works of writers and poets, including Shakespeare, Ovid, Homer and Tennyson.

Waterhouse's best known painting is probably The Lady of Shalott (1888). I've not chosen that as an illustration of his work because it's so well known that it somehow swamps appreciation of the artist's other creations. A painting which due to its familiarity comes with such a lot of baggage that I think we no longer look at it critically, if that makes sense. (See also The Mona Lisa.) I've picked instead The Favourites of the Emperor Honorius (1883).

Another example of Waterhouse's work (The Siren,1900) is below.

These picks of favourite artists appear weekly on my Facebook page.

PHOTOGRAPH OF THE MONTH (57)

Oxfordshire at harvest time.

You can view all the previous Photographs of the Month in the Photo Gallery.

FAVOURITE ARTISTS 3

Continuing the rundown of some personal favourite artists, brought over from my Facebook page, where I post one choice each week, along with a couple of examples of their work. If you want to view all the entries from number one, scroll down to the June update below.

Favourite Artists # 9

ED EMSHWILLER (1925-1990).

Signing most of his work as by “Emsh”, Emshwiller was a prolific science fiction artist, working extensively in the field between 1951 and 1979, and later an experimental film pioneer. Due to his attraction to different art techniques there was never a definitive Emsh style.

Emsh became active as an underground film maker in the mid-60s, the controversial short Relativity (1966) probably being his best known work in that period. He was also a cinematographer on a number of documentaries, including a segment in the Bob Dylan documentary Don't Look Back, and several feature films.

A winner of the Best Artist Hugo award in 1953 (shared with Hannes Bok, number 2 in this Favourite Artists series), Emsh was married to science fiction author Carol Emshwiller (1921-2019).

Favourite Artists # 10

WALLACE (ALLAN) WOOD (1927-1981).

Few people would dispute that artist/writer and independent publisher Wally Wood was a giant of the comicbook industry. Apart from working for virtually every major comics publisher, he illustrated numerous magazines and books, record album covers, trading cards, cartoon strips and one-off cartoons, posters and advertising campaigns. Generally called Wally by readers and fans, he is said to have disliked the name and was known in the industry as Woody. Much of his artwork was simply signed “Wood”.

Subject to recurring, undiagnosed headaches for most of his adult life, his health took a downward turn in the 1970s, with alcohol abuse and kidney failure. In 1978 a stroke cost him his sight in one eye. His career and well-being in decline, on 2nd November 1981 Wood shot and killed himself in Los Angeles. According to an interview he granted shortly before his suicide, and referring to the years of hard, meticulous work he poured into his career, and perhaps the paucity of rewards, he said “If I had to do it all over again I'd cut my hands off.”

He was the first inductee into the Jack Kirby Hall of Fame (1989) and inducted into the Will Eisner Hall of Fame in 1992.

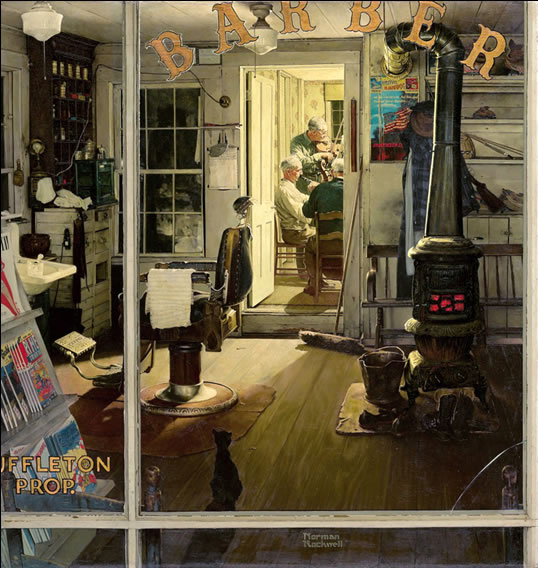

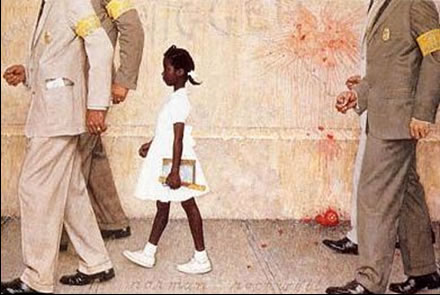

Favourite Artists # 11

NORMAN (PERCEVEL) ROCKWELL (1894-1978).

Arguably the most celebrated illustrator of Americana, Norman Rockwell produced over 4000 artworks, including almost five decades worth of covers for The Saturday Evening Post. He also illustrated more than forty books, along with film posters, postage stamps, playing cards, sheet music, retail catalogues and several murals. His art was commissioned by a number of major companies for advertising campaigns.

Critics tended to dismiss his work as overly sentimental or “too sweet”, and it was only toward the end of his life and posthumously that it began to be regarded seriously. Many of his canvases are now widely exhibited in prestigious art galleries. Steven Spielberg and George Lucas own Rockwell originals.

This piece, Shuffleton's Barbershop, dates from 1950 (and was the inspiration for 2013 TV movie A Way Back Home). The second example, The Problem We All Live With (1964) demonstrates Rockwell's willingness to engage with serious social issues.

Favourite Artists # 12

JOHANNES VERMEER (aka Jan Vermeer;1632-1675) is considered one of the greatest of the Dutch Golden Age artists, although he's thought to have produced only fifty to sixty paintings, of which thirty-four are known to have survived. His modest output is attributed to his slow, meticulous work practises, and the fact that his main occupation was as an art dealer. Vermeer never left Holland, and during his lifetime his fame was almost entirely restricted to Delft, the city of his birth. The destruction caused by the French-Dutch war and the Third Anglo-Dutch war of the 1670s brought financial ruin to many, and Vermeer was no exception. In the years that followed he struggled to support his wife and eleven children, partly by working as an inn keeper, and he died in debt. Vermeer was more or less forgotten after his death, until his rediscovery in the 19th Century, at which point his reputation began to grow.

Perhaps I'm contrary, but I've never been overly keen on his most celebrated work, Girl With a Pearl Earring (1665), much preferring his depiction of scenes from domestic life such as The Music Lesson, Girl Reading a Letter at an Open Window, The Wine Glass and this painting, The Milk Maid (c1658). A close-up of part of The Milk Maid is reproduced below to highlight Vermeer's incredible attention to detail.

Bonus extra. The Milk Maid “modernised version”, a parody by my sister-in-law the artist Janet Calderwood.

PHOTOGRAPH OF THE MONTH (56)

Summer's here, and this is how England looks … when it isn't raining.

All previous Photographs of the Month can be found in this site's Photo Gallery.

FAVOURITE ARTISTS 2

Late 60s self-portrait by artist Al Williamson

In last month's update I began moving over a series of weekly posts from my Facebook page about some of my favourite artists. The first four posted in the June update were Hal Foster, Hannes Bok, Margaret Brundage and Virgil Finlay, which you can see by scrolling down this page. At some future point I hope to gather all these entries in a gallery here. Meantime, here are the next four:

Favourite Artists # 5

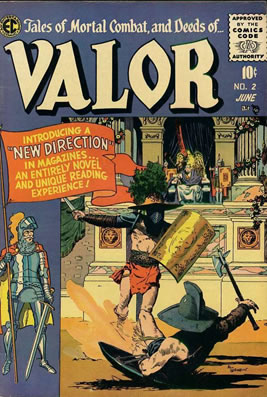

AL(FONSO) WILLIAMSON (1931-2010).

Al Williamson worked primarily as a comicbook artist, specialising in the science fiction, fantasy and western genres. He's noted for his 1950's strips for the EC comics Weird Science and Weird Fantasy, and several other of the company's titles, including Valor. The 1960's saw him continue the comicbook adventures of Flash Gordon, as originally conceived by his artistic idol and inspiration Alex Raymond. He was also an early contributor to Creepy and Eerie, Warren Publishing's black and white horror magazines. From the 1980's to 2003 he worked as an inker, mostly for Marvel Comics, on titles featuring Spider-Man, Daredevil and other popular superheroes. In 2000 Williamson was inducted into the Will Eisner Comicbook Hall of Fame.

Favourite Artists # 6

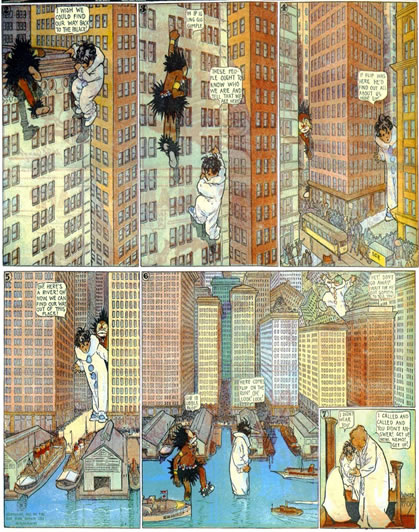

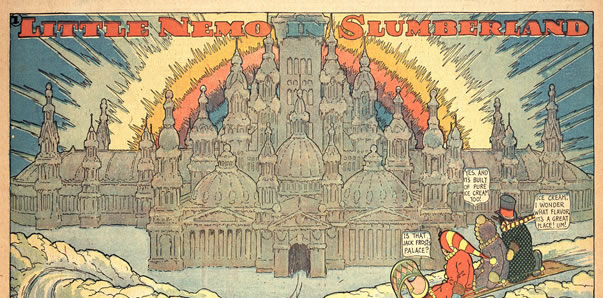

(ZENAS) WINSOR McCAY (1866-1934).